So, first, an exhortation about disunity. How do we approach this problem? Positing solutions seems simplistic from the beginning because of how pervasive and overwhelming a problem schisms have proven to be throughout Church History; but as always, solutions usually begin on the individual level. Verse 10 simply says “Now I exhort you, brethren, by the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, that you all agree and that there be no divisions among you, but that you be made complete in the same mind and in the same judgment.” Considering what was actually happening among the Corinthian fellowship, that seems an astonishing and somewhat naïve thing to say. The immediate issues which leap to mind in protest might be the moral ones, since heinous familial sexual misconduct, divorce, temple prostitution and reckless litigation could all be named among the Corinthian fellowship.

But the doctrinal problems were no less severe. Beyond their eschatological confusion (1 Co. 4:5-8), they denied the existence of a resurrection, and probably the resurrection of Christ Himself (1 Co. 15)! In the face of such flagrant moral and doctrinal meandering, one might wonder how Paul could even assume he was speaking to brethren at all – yet the exhortation in verse 10 addresses them as such. Lest we try to excuse Paul’s inclusive attitude by characterizing the Corinthians as simply “confused” or “mistaught”, consider that Paul’s apostleship was in question, and his ministry under skeptical scrutiny by the fledgling congregation (1 Co. 4:3-4, 9:3). But the opening of the letter in verse 2 proves that this knowledge didn’t hinder Paul from seeing the Corinthians as “saints by calling” who, “with all those in every place, call upon the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, their Lord and ours.” Christian standards of conduct were in decay, and the doctrinal situation was in dire straits, and yet Paul consistently regarded the Corinthains as a Spirit filled family of faith because of their professed allegiance to Jesus as their only Lord and King (cf. 1 Co. 12:3).

Even though he could have declared the Church an apostate fellowship comprised of doctrinal miscreants, he continued to regard them (and exhort them) as family – they were a severely dysfunctional family, but they were “brethren” nonetheless. It’s interesting to note that in nearly every case Paul uses these words, “I exhort you”, he appeals to the familial nature of their relationship (Ro. 12:1, Ro. 15:30, Ro. 16:17, Phil. 4:1-2, 1 Thess. 5:14 and 1 Tim. 5:1). Perhaps the best example of the spirit behind this kind of exhortation is in Philemon 9-10: “yet for love’s sake I rather appeal to you [same word] —since I am such a person as Paul, the aged, and now also a prisoner of Christ Jesus— 10 I appeal to you for my child, whom I have begotten in my imprisonment, Onesimus.”

Yet Paul’s heart for unity wasn’t simply motivated by sentimental familial ties or a desire to “keep the peace at all costs”. The exhortation in verse 10 isn’t just based on their relationship as “brethren”, but on the “name of the Lord Jesus Christ.” Jesus’ name, of course, calls to mind who He is, what He’s done for us, and at minimum, His teaching. Jesus taught His disciples to be One, and to distinguish themselves from the world by their mutual love for one another (Jn. 13:34-35). Thus Paul’s desire for their unity was motivated primarily out of a holy zeal for Christ’s own reputation, which the Church sullies by the arrogance of her divisions. And this is Paul’s ultimate concern – the reputation of Jesus Christ. In order to secure this kind of obedience, he commends three practices for their fellowship to embrace at the individual level: 1) “that you all agree”, 2) that “there be no divisions among you” and 3) that “you be made complete in the same mind and the same judgment.”

1) YOU ALL MUST AGREE: Many of the words found in this passage are political terms; the word for “divisions” in vs. 10, quarrels in vs. 11 and the slogans of vs. 12 (I’m for Paul! I’m for Apollos!) all speak to the issue of party loyalty. Literally, the phrase “that you all agree” reads: “that you all say the same thing” (cf. the NKJV); but the NAS decided to translate it “that you all agree” because “saying the same thing” was a political euphemism for speaking about two or more parties setting aside individual differences to cooperate toward shared ends. This socio-rhetorical background for the language employed in verses 10-17 should dispel the notion that Paul is calling for a Borg-like doctrinal similitude among the Corinthian congregation. Far from “repeating the same doctrinal formulation”, “saying the same thing” involves, “taking the same side.” This shouldn’t be construed as mere compromise – it’s not asking people within various political groups to hide or minimize their differences. They can and should continue to engage in vigorous intramural debate –but the emphasis in this leg of Paul’s exhortation is on keeping the group together by focusing on areas which one can truly “say the same thing” for the sake of accomplishing mutual goals. In all the church’s wrestling through doctrinal and moral crises Paul is commending an attitude that sees one another as essentially on the same side – that of the Gospel of Jesus’ cross (1:17-18). The Church is defined by it’s commitment to a Gospel that proclaims Jesus Christ as Lord of the universe (12:1-3) and that proclaims His death for the forgiveness of sins (15:1-8). If a believer is forced to draw a line in the sand and take sides, Paul says that the only line which exists in God’s eyes is the line between believer and unbeliever (this is exactly Paul’s point in 1 Co. 5:9-13).

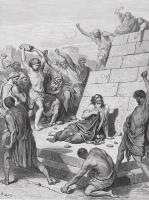

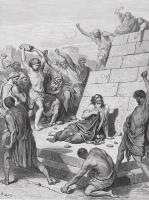

2) LET THEIR BE NO DIVISIONS: Keeping with the first part of this exhortation, the emphasis there is on AMONG YOU. The word “division” is literally, a “tear”, a “gash” or a “rip”. The same word is used in Mt. 9:16, when Jesus speaks of new patches being sewn on old garments. Eventually the patch shrinks and it tears the garment. The imagery of tearing pictures relational discord and ultimately separation. If you’ve been cut from fundamentalist cloth (as I have) the mind must find some way to explain this apparent moratorium on separation. After all, there seem to be circumstances in which separation is commanded, even in this very letter (cf. ch. 5). But Paul’s point here has to do with an illegitimate separation. For those situations that seem as though separation is required, there is one (and only ONE) legitimate way to carry it out: it’s called Church Discipline. This remains the sole mechanism by which the New Testament will authorize division among those who claim the name of Christ. And before this can done (according to Mt. 18), you’ll notice that God demands we plead with the sinning brother 3 times – individually and corporately – before we can introduce separation. When the reluctant disfellowship takes place, we regard such an individual not as “a wayward Christian” or worse, with pious agnosticism about his spiritual state (“we mustn’t fellowship with such a one, but let God judge His heart”) – No, Mt. 18:17 says, “let him be to you as a Gentile and a tax collector.” Thus the line which is to be reinforced among professing believers doesn’t correspond to a camp within Christian doctrine – it is consistently drawn as a separation between believer and unbeliever. Beyond that, Paul says, there are to be no divisions amongst us.

3) SAME MIND, SAME JUDGMENT: In this third and final leg of Paul’s exhortation he suggests the Corinthians be made complete in the same mind and the same judgment. In deliberate contrast with his description of divisions as a “tearing”, this word “be made complete” speaks of sewing back together. Mark 1:19 illustrates the idea in James and John, mending their nets. They weren’t functional while torn, and in order to make them functional again they must be stitched back together, restored to oneness. Instrestingly, the same word is used for “restore” in the context of helping wayward brethren. Gal. 6:1 says “Brethren, even if anyone is caught in any trespass, you who are spiritual, restore such a one in a spirit of gentleness; each one looking to yourself, so that you too will not be tempted.” The same word is also used in 2 Co. 13:11, which should read: “aim for restoration!” Put things back in order, repair what is broken, knit those who disagree back together in mind and in judgment.

Again, in calling the Corinthians to have the “same mind” Paul isn’t saying, “Resistance is futile – you will be assimilated!” He’s talking about a mind-set, a disposition or attitude. It’s a way of thinking. There’s a big difference between sharing

the same opinion on everything and having

the same way of thinking about everything. The former speaks to lockstep conformity with one another while the latter speaks to a shared frame of reference, the same basic pattern of thought. In this case, that same framework is about “the word of the cross”, summarized in 1:18-25 and 15:1-11. There may be different levels of maturity and different stages of apprehension (and hence differences of opinion on various shades of the message), but all share the same basic shape in cruciform worldview.

Doctors may basically agree on how the body works. They may have gone to the same medical schools, taken the same classes from the same teachers, read the same textbooks and still come to completely different conclusions. Yet, one doctor may think that diabetes has some genetic link to ethnicity while another may passionately disagree, seeing diabetes as entirely diet related. Yet one wouldn’t reserve the title “doctor” for the doctor with whom she happens to agree. They both share the same basic framework in practicing medicine, and they could likely even work in the same office with their disagreements. Hopefully both are open to reevaluation on the basis of the available data. In the same way, Christians can share the same basic framework – the Gospel – and even respect the same teachers, go the same schools, read the same Bible, and still come to completely different conclusions on a hundred different important issues. They have the same renewed mind, but they don’t necessarily agree on everything.

The issue, then, becomes a matter of disagreeing agreeably; to have debate without division. Charles Spurgeon, in a semon entitled “A Defense of Calvinism”, called this “Christian courtesy”:

Most atrocious things have been spoken about the character and spiritual condition of John Wesley, the modern prince of Arminians. I can only say concerning him that, while I detest many of the doctrines which he preached, yet for the man himself I have a reverence second to no Wesleyan; and if there were wanted two apostles to be added to the number of the twelve, I do not believe that there could be found two men more fit to be so added than George Whitefield and John Wesley. The character of John Wesley stands beyond all imputation for self-sacrifice, zeal, holiness, and communion with God; he lived far above the ordinary level of common Christians, and was one of whom the world was not worthy. I believe there are multitudes of men who cannot see the truths, or at least, cannot see them in the way in which we put them, who nevertheless have received Christ as their Saviour, and are as dear to the heart of the God of grace as the soundest Calvinists in or out of heaven."

Higher words were never spoken of Wesley, and that from the mouth of one of history’s staunchest Calvinists!

The NIV translates the word judgment, “thought” and the NLT says “have the same purpose” – the reason why it can be translated “judgment”, “thought” or “purpose” is because having the same thoughts or judgments imply that you have the same intent, or the same goal. That’s what this word means – it means “purpose.” So by asking that we have the same “judgment” Paul is calling Christians to rally around their missional mandate, which is of course our Gospel proclamation of Jesus Christ as Lord and King. Recall the doctor analogy again and consider that their differing views on diabetes don’t hinder them from carrying out the task for which they’ve directed their lives: treating and healing the sick. All their vigorous debate about genetics and diet aside, both want to heal those with diabetes. Few medical professionals suffer from the tragic pettiness that Christians do in their doctrinal disputes. The world would not forgive society's most celebrated physicians for neglecting the sick in order to quibble with one another in their university lounges.

So, here is the first resource in dealing with disunity – take personal heed to this exhortation. Don’t ignore the issues. Don’t be afraid to talk about your disagreements. If you are and your debate partner are both humble and teachable, you may actually end up agreeing with one another. But even if you both don’t end up fully agreeing, (and obviously that can happen no matter how humble and teachable you both are), you can still learn from one another and grow from your edification of one another. To put it Paul’s way in this letter, “Knowledge makes arrogant, but love edifies (1 Co. 8:1).” “Seek to abound for the edification of the church (1 Co. 14:12)” and “Let all things be done for edification (1 Co. 14:26)”. When you get frustrated or suspicious with another believer for reasons moral or doctrinal, remember that unless such a one has been the object of the final stages of church discipline, you’re on the same team! Don’t be quick to draw lines of division between you and other people unless you’re willing to declare them an unbeliever (in which case you should think about the judicial processes that are to precede such a declaration). Guard yourself from the glib put-downs and air of superiority which may prevent you from fellowshipping with Christians of a different stripe. Refuse to take sides or force other people to take sides against other believers in the body. That’s not discernment - it's the definition of schismatic, divisive, factious behavior, and it’s never a godly thing to do. Go, in love, to confront those in sin with the purpose of their edification; patiently work with them and pray for them to learn and grow, and if they continue to live in sin, with a broken-heart full of hope in their restoration, initiate church discipline. But if those with whom you have conflict with are born-again, God will never sympathize with one group taking sides against the other. Let the only dividing line in your life be between believers and unbelievers.

Seek to heal division within the fellowship, not create it. Instead of trying to force separation between believers in the name of “discernment”, do the harder work of seeking to bring them together around the same mission. Have the same mind and the same purpose that’s supremely concerned with the work of the Gospel, both among us and in the world. Spend your energy, time and resources partnering together with one another in accomplishing that mission. Concentrate your ministry on tearing down unbelieving strongholds in the world. Focusing our attention there leaves us for no time for division, as there’s plenty of work to be done.

Being a family is hard work because we’re all naturally selfish and proud. It takes a lot of humility to learn from one another, love to cover over a multitude of sins, patience as we are sinned against, and endurance with people that are slow to change. But we’re committed to doing that in our families, because without strong families, society decays. The Church is the most important family there is – it’s the hope of the world’s salvation, and its family Jesus died to create.

When considering the exhortation of 1 Corinthians 1:10, maybe your picture of what a factious person looks like is something like the Neighborhood Watch villain. He’s easy to spot and, of course, he doesn’t look anything like us. Knowing our own hearts such as we do, and giving ourselves the benefit of the doubt, we recoil at the idea that such a word could possibly apply to us without overstating the case. We may be rough or over-zealous at times; but typically we reserve this sort of terminology for King James Only people, or hyper-Calvinists, or maybe Rick Miesel. And while these assessments would be correct, Paul's down-to-earth description of disunity in verses 11-12 should give us pause. The extremities of sinful behavior too easily serve as distractions from the very same roots which lie in our own hearts.

When considering the exhortation of 1 Corinthians 1:10, maybe your picture of what a factious person looks like is something like the Neighborhood Watch villain. He’s easy to spot and, of course, he doesn’t look anything like us. Knowing our own hearts such as we do, and giving ourselves the benefit of the doubt, we recoil at the idea that such a word could possibly apply to us without overstating the case. We may be rough or over-zealous at times; but typically we reserve this sort of terminology for King James Only people, or hyper-Calvinists, or maybe Rick Miesel. And while these assessments would be correct, Paul's down-to-earth description of disunity in verses 11-12 should give us pause. The extremities of sinful behavior too easily serve as distractions from the very same roots which lie in our own hearts. So far so good; but I suspect that our eyes are still on the branches instead of the roots. What we often fail to recognize is that no one prefers to thinks of themselves as “loving quarrels”. In fact, most of the time we engage in quarrels it’s because we think we’re doing something else - we’re championing the truth against the various manifestations of liberalism, we're standing for God and the Bible in times when it's unpopular to do so, we're being faithful to the Scriptures, come Hell or highwater . . . and so on. But bickering about the truth can still count as quarreling. And this, unfortunately, is often our speciality.

So far so good; but I suspect that our eyes are still on the branches instead of the roots. What we often fail to recognize is that no one prefers to thinks of themselves as “loving quarrels”. In fact, most of the time we engage in quarrels it’s because we think we’re doing something else - we’re championing the truth against the various manifestations of liberalism, we're standing for God and the Bible in times when it's unpopular to do so, we're being faithful to the Scriptures, come Hell or highwater . . . and so on. But bickering about the truth can still count as quarreling. And this, unfortunately, is often our speciality. In order for our disputes to be spiritual, they must display the fruit of the Spirit. That means that our words, attitudes and even our study should be saturated with love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control; and it should display not just one of these things – just faithfulness, for example – but all of them. Don't let the radical nature of that claim escape you! Imagine what our study (much less our disputes) would look like if it were characterized by the love described in 1 Co. 13; and that's just one of the nine qualities of the Spirit's yield.

In order for our disputes to be spiritual, they must display the fruit of the Spirit. That means that our words, attitudes and even our study should be saturated with love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control; and it should display not just one of these things – just faithfulness, for example – but all of them. Don't let the radical nature of that claim escape you! Imagine what our study (much less our disputes) would look like if it were characterized by the love described in 1 Co. 13; and that's just one of the nine qualities of the Spirit's yield.