Certainly, doctrine (defined as the work of godly teachers of the Bible) contributes much to the Christian life. But in some ways, according to Scripture, the Christian life is prior to doctrine in this sense. As Jesus told Nicodemus (“the teacher of Israel,” John 3:10), you can’t even see the kingdom of God unless you are born again (John 3:3), that is, unless you have new life from God (cf. 1 John 2:29; 3:9; 4:7; 5:1, 4, 18). You cannot be a teacher unless God has given you new life. Through that new life, God gives you a “willingness to do his will” that enables you to know the truth of Jesus’ teaching (John 7:17). Note that here a change of life is prior to a change in intellectual orientation, a change in doctrine.

Note also how the Apostle Paul tells us to find, test, and approve the will of God in Romans 12:1–2: by making our bodies living sacrifices, renouncing conformity to the world, being transformed by the renewal of our minds. Again, a change of life is what brings insight, doctrinal understanding. Compare in this respect 1 Corinthians 8:1–3 (where love and humility are indispensible prerequisites to knowledge); Ephesians 5:8–10 (where living as children of light leads us to find what God’s will is); Philippians 1:9–10 (where love gives insight); and Hebrews 5:11–13 (where ethical maturity prepares us to benefit from doctrinal teaching about Melchizedek).

So theology is not self-sufficient. It depends on the maturity of your Christian life, as the maturity of your Christian life depends on theology. Growth in grace will make you a better theologian, and becoming a better theologian will help you grow in grace. There is a “spiral” relationship between the two. When you become a Christian, you usually get some elementary theological teaching, a great help in getting started in your walk with the Lord. But then new questions arise, and you go back to Scripture and theology, and you get more advanced answers—sometimes to the same questions you had as a spiritual babe. But your greater maturity enables you to understand and appreciate teaching of greater depth. And that teaching, in turn, helps you to grow more, and so on.

This is why, in the New Testament, the qualifications of teachers (1 Timothy 3:1–7; Titus 1:5–9) are more spiritual than intellectual. Paul mentions “aptness to teach” and “sound doctrine,” but his qualifications for elder-teachers are mostly ethical: “above reproach, the husband of but one wife, temperate,self-controlled,” etc. The application is obvious: If you want to become a theologian, you must be a godly person. That principle applies to the most academic and theoretical of theologians, as well as to the practical theologians (like most of you) who preach sermons, lead Bible studies, nurture other believers, and witness to the lost.

Wednesday, October 31, 2007

A Priority of Doctrine in Christian Living?

Wednesday, June 13, 2007

Gospel Sex

7:1 Now concerning the matters about which you wrote: “It is good for a man not to have sexual relations with a woman.” 2 But because of the temptation to sexual immorality, each man should have his own wife and each woman her own husband. 3 The husband should give to his wife her conjugal rights, and likewise the wife to her husband. 4 For the wife does not have authority over her own body, but the husband does. Likewise the husband does not have authority over his own body, but the wife does. 5 Do not deprive one another, except perhaps by agreement for a limited time, that you may devote yourselves to prayer; but then come together again, so that Satan may not tempt you because of your lack of self-control.”

This is a passage that has often been used by husbands to shift the burden of responsibility for their immorality onto their supposedly under-sexed wives. Pastors are not immune. Countless counseling situations are seen through the lenses of sexually frustrated men, quick to quote these verses, and leave it at that. But Paul won’t have it. If your husband does that, simply take him back to 1 Co. 6:16-17 where Paul compares being “one flesh” with a woman with being “one spirit” with Jesus. What that assumes is that the sex he’s talking about in this chapter isn’t the same thing as the immorality he condemned in chapter 6 – the self-serving, get-your-needs-met-and-roll-over kind of sex; “food is for the body and the body for food”. This is Hebrew sex; not just the uniting of two bodies but the uniting of two souls, the mingling of two lives. It’s an act of physical oneness that mirrors, pictures, illustrates, embodies, incarnates a spiritual oneness. It’s Gospel sex, a reflection of the oneness we have with Jesus by the Holy Spirit.

This is a passage that has often been used by husbands to shift the burden of responsibility for their immorality onto their supposedly under-sexed wives. Pastors are not immune. Countless counseling situations are seen through the lenses of sexually frustrated men, quick to quote these verses, and leave it at that. But Paul won’t have it. If your husband does that, simply take him back to 1 Co. 6:16-17 where Paul compares being “one flesh” with a woman with being “one spirit” with Jesus. What that assumes is that the sex he’s talking about in this chapter isn’t the same thing as the immorality he condemned in chapter 6 – the self-serving, get-your-needs-met-and-roll-over kind of sex; “food is for the body and the body for food”. This is Hebrew sex; not just the uniting of two bodies but the uniting of two souls, the mingling of two lives. It’s an act of physical oneness that mirrors, pictures, illustrates, embodies, incarnates a spiritual oneness. It’s Gospel sex, a reflection of the oneness we have with Jesus by the Holy Spirit. And that intimates the shocking suggestion that the reason your wife isn’t as willing as you are “to be intimate” is because you don’t want intimacy. You want to share your body, but not so much your soul. You want to receive pleasure, but you don’t want to receive your wife – her problems, her pains, her joys, her hopes, her sorrows. You have all the expectations of a sexual Gnostic, as though your wife’s body could be separated from her soul. You don’t really want to be “one flesh” – you just want to have sex. And the problem with that is that this is not the sort of marriage that will protect you from sexual immorality, because if that’s all you want, what’s the difference between sex with your wife and sex with anyone else? You’re trying to fight your selfish lust in the world with your selfish lust at home. How can you break your addiction to selfish sexual pleasure unless you begin to see your sexual acts as about a person instead of an orgasm? It won't work. Anyone can give you pleasure. You don’t need your wife for that. You can do that on your own. If you want to experience the kind of sex that will deliver you from your sinful lusts, you’re going to have to start acting like you’re married someplace other than the bedroom. You’re going to have to stop chasing the cheap imitation of sex-without-relationship (what the Bible calls "immorality) and start drinking deeply from your wife.

And that intimates the shocking suggestion that the reason your wife isn’t as willing as you are “to be intimate” is because you don’t want intimacy. You want to share your body, but not so much your soul. You want to receive pleasure, but you don’t want to receive your wife – her problems, her pains, her joys, her hopes, her sorrows. You have all the expectations of a sexual Gnostic, as though your wife’s body could be separated from her soul. You don’t really want to be “one flesh” – you just want to have sex. And the problem with that is that this is not the sort of marriage that will protect you from sexual immorality, because if that’s all you want, what’s the difference between sex with your wife and sex with anyone else? You’re trying to fight your selfish lust in the world with your selfish lust at home. How can you break your addiction to selfish sexual pleasure unless you begin to see your sexual acts as about a person instead of an orgasm? It won't work. Anyone can give you pleasure. You don’t need your wife for that. You can do that on your own. If you want to experience the kind of sex that will deliver you from your sinful lusts, you’re going to have to start acting like you’re married someplace other than the bedroom. You’re going to have to stop chasing the cheap imitation of sex-without-relationship (what the Bible calls "immorality) and start drinking deeply from your wife.Beware arming yourself with the Bible in order to batter your spouse and feed your own flesh: it’s like a sword without a hilt or a handle – it cuts even the ones who wield it. Take it from one whose hands have been bloodied.

Friday, May 25, 2007

Are Debates with Atheists Good for the World?

Christianity Today recently began a series on the topic, “Is Christianity Good for the World?” – a subject which turns out to relate to my previous post more than tangentially. Pearcey’s main contention, after all, is that the atheistic materialist really has no warrant for lauding lofty humanistic values given their mechanistic and deterministic view of the universe; and this observation has been the focal sticking point of the entire exchange.

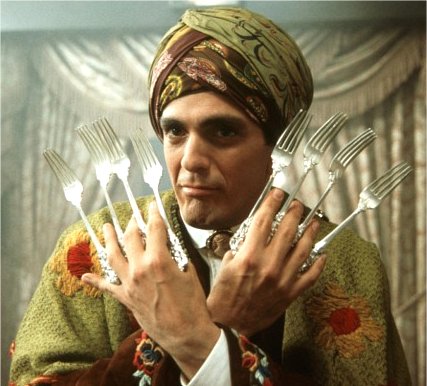

Christianity Today recently began a series on the topic, “Is Christianity Good for the World?” – a subject which turns out to relate to my previous post more than tangentially. Pearcey’s main contention, after all, is that the atheistic materialist really has no warrant for lauding lofty humanistic values given their mechanistic and deterministic view of the universe; and this observation has been the focal sticking point of the entire exchange.The champions called to do battle are an odd pair of obviously mismatched pedigree, an observation humbly noted by the affirmative position (fellow Idahoan, Doug Wilson). Maybe that’s what makes the ensuing discussion such an embarrassment for the negative thus far. Beyond the usual frustration in such “conversations”, where mis-characterizations abound, one gets the distinct impression that Christopher Hitchens is so confident that he’s interacting with an idiot that he doesn’t bother to formulate a single argument. Instead, not unlike our favorite-fork-flinging hero, he unleashes a torrent of verbal cutlery aimed to humiliate the religiously inclined. His attacks are debonair, but rarely of any serious substance – which is where my frustration lies with this larger “down with God” publishing trend we’re seeing lately.

At the point we need philosophers and theologians we are served with self-inflating pundits (or, as in the case of Dennett, philosophers who refuse to engage religion philosophically). Were it not for their impressive vocabularies, it might be more obvious that the “debates” presented in these forums are more like a re-run of Sally Jesse Raphael than they are serious philosophical symposiums. The academic forbearers upon which the edifice of Western society rests (people like Augustine, Aquinas and Pascal) are gaily waved away without protest by people like Hitchens, choosing instead to best Bill O’Reily and Sean Hannity on promotional book tours. The call for a “new enlightenment” conveniently forgets the Christian resources by which we got the first one. He wishes to rise from the ashes of institutions and ideas which, though singed, still stand strong both academically and popularly. Even Nero waited for the city to burn before playing his violin.

Leon Wieseltier’s evaluation of Dennet’s Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomena in The New York Times could just as aptly describe what I’ve seen of Hitchens in this interchange:

Leon Wieseltier’s evaluation of Dennet’s Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomena in The New York Times could just as aptly describe what I’ve seen of Hitchens in this interchange:And Dennett's book is also a document of the intellectual havoc of our infamous polarization, with its widespread and deeply damaging assumption that the most extreme statement of an idea is its most genuine statement. Dennett lives in a world in which you must believe in the grossest biologism or in the grossest theism, in a purely naturalistic understanding of religion or in intelligent design, in the omniscience of a white man with a long beard in 19th-century England or in the omniscience of a white man with a long beard in the sky.If you haven't read the exchange, follow the link and catch up - I'm curious to hear your reactions.

Sunday, March 11, 2007

Do You Believe in Truth? Totally.

I recently read Nancy Pearcey's Total Truth and have decided to post a sort of review in a series of reflections on the book.

I recently read Nancy Pearcey's Total Truth and have decided to post a sort of review in a series of reflections on the book. Adding to a recent treasury of books aiming to reinvigorate the evangelical mind[1] is Nancy Pearcey’s Total Truth: Liberating Christianity from Its Cultural Captivity. Whereas other treatments of evangelical mental laxity and compromise have focused on particular issues, most recently politics[2], Pearcey stakes out a task both more admirable and difficult; the critique and construction of an entire worldview. A bevy of books have been published in this area to be sure, but what distinguishes Total Truth is its concern for broad application of a Christian worldview. In just under 400 pages the lay reader is initiated into topics ranging from analytic philosophy (metaphysics, epistemology, philosophy of science), political philosophy, cosmology, cosmogony, biology, early American religious nationalism and the intellectual history of the Western world (replete with sociological implications for the church and the world). Were it not for the pedagogical dexterity of the author, this could have been a much larger book! But in the spirit of her mentor, Francis Schaeffer (from whom the title of the book hails), Nancy Pearcey accomplishes something just as difficult as any specialized treatment of these subjects – a conceptual analysis that is actually recognizable in real life. Indeed, the only thing more breathtaking than the breakneck pace with which these topics are covered is just how easily her assessments can be seen in American culture.

The cleavage introduced by the strict “scientific” standards for public truth places the top story in the relativistic flux of private opinion and personal perspective. Since public truth says that humans are essentially bags of meat deterministically driven by natural law, beliefs about the “human spirit” turn out to be a universally held necessary fiction requiring voluntary self-deception. As chief Wiggum of the Simpsons has eloquently put it, “[the secularist’s] mouth is writing checks his butt can’t cash”.

There's much to like about this approach, which we'll take up in the next few posts. As with any attempt at integration (and that's really the key word for understanding the agenda behind this book) it also involves some reductionistic homogenization. But at the outset I must say that I really enjoyed Total Truth, if for no other reason than Pearcey's deep understanding of evangelicalism's inner contradictions, instinctive dualism and populist anti-intellectualism.

[1] See Mark Noll, George Marsden, Ronald J. Sider, etc.

[2] Two recent examples are David Kuo's Tempting Faith: An Inside Story of Political Seduction and Gregory Boyd's The Myth of a Christian Nation: How the Quest for Political Power Is Destroying the Church.

Saturday, February 24, 2007

This One Deserves It's Own Label . . .

Just caught this over at the BHT and was so impressed that I decided to make up an entirely unique label just for this quote:

Just caught this over at the BHT and was so impressed that I decided to make up an entirely unique label just for this quote:Conservapedia is an online resource and meeting place where we favor Christianity and America. Conservapedia has easy-to-use indexes to facilitate review of topics. You will much prefer using Conservapedia compared to Wikipedia if you want concise answers free of "political correctness".

Wednesday, February 14, 2007

Sola Plerusque?

Some people wear the "5 Sola's" as a badge of honor. Affiliating oneself with the Reformers, after all, is very much like asking to sit at the right and left hand of Jesus. It struck me (on the toilet, actually - how's that for affiliating myself with the Reformation) how absurd it is to pluralize the word "alone". Was there such a thing as math in 16th C. Western Europe? It seems like for the five affirmations to make any sense they would have to be punctuated by the word "or". Is it Scripture alone? Or is it Christ alone? Or is it grace alone? Or is it faith alone? Or is it only to God that the glory belongs?

Some people wear the "5 Sola's" as a badge of honor. Affiliating oneself with the Reformers, after all, is very much like asking to sit at the right and left hand of Jesus. It struck me (on the toilet, actually - how's that for affiliating myself with the Reformation) how absurd it is to pluralize the word "alone". Was there such a thing as math in 16th C. Western Europe? It seems like for the five affirmations to make any sense they would have to be punctuated by the word "or". Is it Scripture alone? Or is it Christ alone? Or is it grace alone? Or is it faith alone? Or is it only to God that the glory belongs?Now, obviously these "alone's" aren't functioning the same way in each of these mottoes - Scripture alone is the rule of the Church's life while Jesus alone is the source of our salvation and grace alone is the ground of said salvation; faith alone is the only means by which it can be received and the credit for all of this can only be attributed to God. What those clarifications demonstrate, though, is just how insufficient the word "alone"really is to describe something as rich and complex as God's plan of salvation.

Each "sola" is so porous that they could never serve as firm doctrinal boundaries; a fact which is easily seen in the constant haggling in Reformed circles over whether one of the sola's has truly been transgressed or not. What does it even mean for God to receive all the glory? Don't believers share in that glory by virtue of our union with Christ? And what about "faith alone" and "grace alone"? The complex relationship between faith and works is almost universally described as involving some kind of necessary dependence (even if that dependence is the construal of works as the necessary outgrowth of faith) - so Lordship salvation somehow can be held without denying this sola while those who entirely stand on it can be soundly rejected. The role of the Scriptures as an authority has been the center of just as much controversy, since it's not clear exactly HOW Scripture should function as an authority (the regulative principle being one example of this question). Obviously countless examples could be given (does Wayne Grudem deny sola Scriptura in his view of prophecy?) - but I'm left wondering exactly what the practical value of these slogans are.

Wednesday, January 24, 2007

Interview with Dr. Peter Enns

Dr. Peter Enns is the professor of Old Testament and Biblical Hermeneutics at Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia. He's the author of the NIV Application Commentary on Exodus and contributed to the D.A. Carson edited Justification and Variegated Nomism, Vol. 1: The Complexities of Second Temple Judaism with his excellent essay on expansions of Scripture. I recently had an email exchange with Dr. Enns, whose most recent book Incarnation and Inspiration: Evangelicals and the Problem of the Old Testament I reviewed in three parts (which are available here, here and here). Actually, it might be more accurate to say that I responded to some other reviews - the book in question has raised no small amount of controversy in the Reformed world. Having recognized popularly prevailing gnostic notions of Biblical inspiration, Enns seeks to balance the equation with a robust explanation of Scripture's humanity - not with a view to canceling out it's divine nature, but in the hopes of deriving a nuanced analogy with the incarnate Word of God Himself. In our exchange he kindly agreed to be interviewed for the blog, which I promised my readers I'd reproduce here earlier this month.

Dr. Peter Enns is the professor of Old Testament and Biblical Hermeneutics at Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia. He's the author of the NIV Application Commentary on Exodus and contributed to the D.A. Carson edited Justification and Variegated Nomism, Vol. 1: The Complexities of Second Temple Judaism with his excellent essay on expansions of Scripture. I recently had an email exchange with Dr. Enns, whose most recent book Incarnation and Inspiration: Evangelicals and the Problem of the Old Testament I reviewed in three parts (which are available here, here and here). Actually, it might be more accurate to say that I responded to some other reviews - the book in question has raised no small amount of controversy in the Reformed world. Having recognized popularly prevailing gnostic notions of Biblical inspiration, Enns seeks to balance the equation with a robust explanation of Scripture's humanity - not with a view to canceling out it's divine nature, but in the hopes of deriving a nuanced analogy with the incarnate Word of God Himself. In our exchange he kindly agreed to be interviewed for the blog, which I promised my readers I'd reproduce here earlier this month.Here it is!

Raja: Can you say a few words about the theological tradition that you currently inhabit and why it’s important to you?

Dr. Enns: As a young Christian I was introduced to the Reformed faith quite “accidentally” by stumbling into a PCA church in central

Raja: What are some conscious weaknesses of the tradition which inform your own work?

Dr. Enns: Well, any tradition has weaknesses, since we are all fallen creatures and articulate truth imperfectly. What I greatly admire about the Reformed faith in general is intellectual depth and breadth, which are of great service to the God’s people. But that strength has also been a weakness: when combined with spiritual immaturity it can lead to spiritual pride expressed in an uncharitable or even condescending tone toward other Christians who do not share those convictions or who do not hold them in the same sort of way. I think the Reformed faith needs to be extra careful to reflect Christ’s humility and think of its great tradition as a tool more than a weapon.

Raja: Is there a theological tradition outside your own that you particularly appeciate?

Raja: Is there a theological tradition outside your own that you particularly appeciate?

Dr. Enns: I appreciate different traditions for different reasons, and I feel that the various traditions all have things to learn from each other while also offering criticism when necessary. I wouldn’t say there is any one or two that make the top of my list; I try to maintain a posture of open-mindedness toward other Christians while also embracing the tradition to which I have committed myself. C. S. Lewis’s analogy in the preface to Mere Christianity has always struck me as a healthy, mature, Christian outlook. He speaks of Christianity is a grand hall out of which doors open into several rooms. We are not meant to live in the hall for long but to choose the door that we are convinced best reflects the truth. But, as Lewis continues, “When you have reached your own room, be kind to those who have chosen different door and to those who are still in the hall. If they are wrong they need your prayers all the more; and if they are your enemies, then you are under order to pray for them. That is one of the rules common to the whole house.”

Raja: Do you think Christian academics are often insensitive to the needs of the Church, and if so, how do you address this in your own writings?

Dr. Enns: I think they certainly can be insensitive, but it may be a bit of a caricature to hold all of us guilty. Still, I had a conversation with Scot McKnight about this not too long ago and he reminded me that, in the not too distant past (before the 1970’s), evangelical academics wrote much more to lay audiences. It was seen as their duty to write books that people not of the academic guild could benefit from. For whatever reason, McKnight detects a shift in the 70’s where establishing oneself in the academy became more of a priority. It is very hard work to combine a life of rigorous academic work and service to the church at large (add to that how highly specialized the various disciplines have become), but we must try to make that happen (McKnight actually pulls this off very well). But to do so means, for most of us, making decisions about what to publish and where. I would also add that part of the insensitivity can stem from academics failing to remember that they are servants above all. Sometimes we think more of what it is we know and the urgency of bringing all of that at once to people who are not prepared to hear it. If we think first, however, of what will be of benefit to others, it may affect the questions we ask and how we go about answering them.

Raja: To what degree does the evangelical debate over modernism and postmodernism in theology enter your discussion of inspiration in Inspiration and Incarnation?

Dr. Enns: I’m not sure how well that distinction captures it, at least not in a strict academic/philosophical sense of the words, but it may be appropriate from a, let’s say, temperamental point of view. For example, I&I is clearly a missional book, and so lines can be drawn to the emerging movement. I would hope, however, that a missional mindset not be exclusively associated with any one movement. (While I was in seminary, I was encouraged to think along missional lines by my professor Harvie Conn, who was quite intentional about a missional hermeneutic throughout his nearly thirty years at Westminster Theological Seminary) Also, my thoughts on inspiration are deeply influenced by what I refer to in my book as an incarnational approach, which was always lurking in the background in my seminary education, and a desire (begun in seminary and augmented in graduate school) to account for how the Bible looks as a function of its historical contexts. It is a bit interesting to me that these two influences are anything but postmodern: Reformed orthodoxy and training in modern biblical studies. Simply studying the Bible is itself an introduction to a missional hermeneutic (Chris Wright’s recent IVP release The Mission of God: Unlocking the Bible’s Grand Narrative is a wonderful and timely summation of this notion.)

Dr. Enns: I think where the criticism have been most helpful is in pointing out some ambiguities and imprecise (and therefore misleading) aspects of the book. For example, even though I feel I qualify the matter at junctures, I can also see how I can leave the impression that evangelicalism as a whole has been misguided and in need of sweeping correction. I actually say the opposite at the outset and the bibliographies include evangelical authors, but there are a few phrases in the book that fail to make that distinction and have led to understandable confusion. Similarly, the book is not calling for a complete overhaul of Christian doctrine, only a more deliberately positive accounting of its complex human dimension, and how that accounting can influence Christian doctrine. Where I think the book has been most misunderstood is in its missional dimension. I think some critics expect a book that deals with inspiration to have a certain look and use certain vocabulary, and so respond to a book that I actually had no intention to write. Another area where the criticism has been helpful is in helping me articulate more clearly in my own mind where the divide might be among evangelicals, and I think it may have to do with the role historical study plays in how we think about Scripture, or perhaps to what extent historical context will contribute to doctrinal formulations that were made before the serious influx of historical information over the past 150 years or so. That is an exceedingly complex matter to untangle, in my opinion, but it is a task waiting to be done.

Raja: Do you read Christian blogs, and do you see theological blogging as a worthwhile enterprise?

Dr. Enns: If done “right.” Blogs can be helpful if the rhetoric and posturing are toned down. I do not think, however, that the internet is a helpful venue for any sort of really serious theological debate but more of a place for musing and dialog. Debate requires a patience and distance that are not encouraged by the “tyranny of the urgent” inherent on the internet. When we have instant access to others—without the subtleties that accompany a face-to-face meeting—we are more prone to say things that upon further reflection we would likely not say (and email may even be worse). The internet is instant yet impersonal, even anonymous at times. That encourages posturing more than a true meeting of the minds.

Raja: Is there anything else you’d like to say?

Raja: Is there anything else you’d like to say?

Dr. Enns: I’m glad the Yankees got Pettitte back, although I hope his back problems are a thing of the past…. Although I will always owe a deep and inexpressible debt of gratitude to “The Simpsons,” it has been losing its edge for some time now, and so “The Office” has become my favorite TV comedy…. I am really hoping I can stick with my workout schedule for more than two months into the new year.

Friday, January 19, 2007

Thursday, January 18, 2007

A Hegelian Forray into Calvinism

Those who could care less about debates in the Reformed blogosphere, skip this and read the posts below.

Okay, so the title of this post doesn't make any sense, but since the subject of this post is mostly dead around the blogosphere, I had to think of something - not to mention that it sounded smart, and that's enough to prop up my ego (which, let's be honest, is precisely what blogging is all about anyway). But the reason I thought this title might fit was because of what I've seen going on at one of those blogs I read semi-regularly - namely the web-home of Phil Johnson and friends, proudly blogrolled to your right. The atmosphere there lies somewhere between genuinely encouraging and noxiously abrasive - but there's enough of the former to keep me coming back to read the Godward musings of men loosely connected with my alma mater. Beyond the odd (as in occasional) devotional (in a good way) post, every once and awhile something very interesting takes place. Without making any value judgments about it (yet), you'll notice that from time to time some not-so-distant theological cousins show up and wreak the same kind of havoc on the PyroManiacs that others have accused of the PyroManiacs of unleashing on them. A strange role-reversal takes place whereby SOMEONE ELSE plays the role of the PyroManiac TO the PyroManiacs. It's enough to blow your mind, like when you find out that all of the characters John Cusack is interacting with in the movie Identity are actually some demented fat guy.

Man, I'm really not hitting with these analogies today.

In the past it's been those more fundamentalist than Phil and crew, but as of late it's been those who are more professedly Calvinist than the bunch. The kerfuffle erupted over a Francis Chan gospel presentation mentioned at the BHT which, apparently, wasn't hardcore enough for some of TeamPyro's Calvinist readership. The exacting, theologically Pavlovian terminology was conspicuously absent from his presentation, causing some Reformed watchdogs to foam rather than salivate, and the result was a basic defense of the video's integrity on the part of the TeamPyro crew. In a really great series of posts Phil, Frank and Dan all showed their dismay at the hair-splitting over-shrewdness of the critics.

In the past it's been those more fundamentalist than Phil and crew, but as of late it's been those who are more professedly Calvinist than the bunch. The kerfuffle erupted over a Francis Chan gospel presentation mentioned at the BHT which, apparently, wasn't hardcore enough for some of TeamPyro's Calvinist readership. The exacting, theologically Pavlovian terminology was conspicuously absent from his presentation, causing some Reformed watchdogs to foam rather than salivate, and the result was a basic defense of the video's integrity on the part of the TeamPyro crew. In a really great series of posts Phil, Frank and Dan all showed their dismay at the hair-splitting over-shrewdness of the critics.The Pyros insisted that there is essential agreement, objected to vacuous labelling of their nuanced position, protested exaggerations about their view, balked at the bumper-sticker rhetoric being used against them, accused the opposition of not actually reading their posts and called for a greater appreciation for Christian conduct over an obsession with doctrinal precision. The Calvinist vanguard stood their ground, which (of course) was the self-professedly more consistent, more Biblical and more God-exalting position, to the exasperation of their "conversation" partners.

And the broadly-Reformed universe collapsed on itself.

.jpg) This is where my opaque title comes into play - an over-simplified summarization of Hegel's philosophy of history involves a thesis sowing the seeds of its own destruction. Some previous TeamPyro posts (which Phil helpfully linked in his excellent article) warn against what he considers excessive listening and dialog. He's not a big fan of conversation. These posts also warn against being too narrowly divisive, of course - but they fail to create criteria by which someone is being "narrowly divisive" as opposed to "fighting for the Gospel" - instead they supply a kind of ad hoc criteria which defines divisiveness as "anyone to my immediate right" and heresy as "everyone to my immediate left". What becomes clear in all of this is that the Pyro's critics could have easily written the previously linked post about "conversation" with reference to the defenders of Chan. It's this kind of methodological problem that not only allows Phil to characterize me as one of the "doctrinally freewheeling TMS graduates" who "seem enthralled with certain currently-stylish flavors of epistemological skepticism", but also leaves himself wide open to the spirit of his critics' accusations (i.e. that he denies the absolute sovereignty of God, and possibly the Gospel itself).

This is where my opaque title comes into play - an over-simplified summarization of Hegel's philosophy of history involves a thesis sowing the seeds of its own destruction. Some previous TeamPyro posts (which Phil helpfully linked in his excellent article) warn against what he considers excessive listening and dialog. He's not a big fan of conversation. These posts also warn against being too narrowly divisive, of course - but they fail to create criteria by which someone is being "narrowly divisive" as opposed to "fighting for the Gospel" - instead they supply a kind of ad hoc criteria which defines divisiveness as "anyone to my immediate right" and heresy as "everyone to my immediate left". What becomes clear in all of this is that the Pyro's critics could have easily written the previously linked post about "conversation" with reference to the defenders of Chan. It's this kind of methodological problem that not only allows Phil to characterize me as one of the "doctrinally freewheeling TMS graduates" who "seem enthralled with certain currently-stylish flavors of epistemological skepticism", but also leaves himself wide open to the spirit of his critics' accusations (i.e. that he denies the absolute sovereignty of God, and possibly the Gospel itself).

Death to the Pixies

I still remember the first time I caught a glimpse of Frank Black on a poster at the local record store. I had just started getting into The Pixies and the raw wailing of the 90's alternative punk god, my mental projection of him being the typical screaming Seattle waif of a front-man. What I saw was a portly balding lumberjack. The delightful wrongness of that image sort of represents the quirky greatness of The Pixies, and my appreciation for them has only grown as of late. After my conversion to Christ I predictably threw away all of my CD's, including a lot of Pixies I now wish I still owned (it usually takes you a few years in Christ to "get" the idea of common grace). A few years ago I picked up the compilation, Death to the Pixies, in the hopes of replacing what I'd lost in the most economical way possible. The result was both glorious and satisfying.

I still remember the first time I caught a glimpse of Frank Black on a poster at the local record store. I had just started getting into The Pixies and the raw wailing of the 90's alternative punk god, my mental projection of him being the typical screaming Seattle waif of a front-man. What I saw was a portly balding lumberjack. The delightful wrongness of that image sort of represents the quirky greatness of The Pixies, and my appreciation for them has only grown as of late. After my conversion to Christ I predictably threw away all of my CD's, including a lot of Pixies I now wish I still owned (it usually takes you a few years in Christ to "get" the idea of common grace). A few years ago I picked up the compilation, Death to the Pixies, in the hopes of replacing what I'd lost in the most economical way possible. The result was both glorious and satisfying.The compilation consists of two CD's, one recorded and the other live. The recorded CD seemed to be a haphazard selection, with representative tracks from their albums just flung together without any discernible arrangement. But from the opening track I was instantly reminded just how BIG their sound was. The guitars tear at your face and Black's shredding vocals are just as beautiful as I remember. I probably would have chosen a different opening track (Cecelia Ann from Bossonova), but "Planet of Sound" is probably one of my favorite rock songs of all time. One thing I hadn't noticed from my high-school days was the amount of Biblical allusion in their lyrics, with darker themes of Old Testament narrative (like incest and rape) being parodied in various songs ("Nimrod's Son" comes to mind). But the lyrics aren't Marilyn Manson-ish tripe - it's an intelligent wrestling with absurdity that provokes more than it defiles. Much like their lyrics, their explosive vocals and careening guitars never dissipate into chaos or lose their melodic energy.

The live recording shows just how well-deserved their reputation for stellar stage presence really was, with many songs mirroring the tracks on the recorded portion of the compilation. The comparison helps to highlight the points of departure and improvisation ("Wave of Mutilation" is slower, for example). Even though a few songs sound somewhat "phoned in", with "Monkey Gone to Heaven" as an obvious example, there are a number of renditions that make you want to run around flapping your arms like a chicken - "Broken Face" and "Isla De Encanta" chug with all the power of a speeding train. Their incredible sensibilities for pop rock are on full display in "U-Mass", "Dig For Fire" and "Allison".

The live recording shows just how well-deserved their reputation for stellar stage presence really was, with many songs mirroring the tracks on the recorded portion of the compilation. The comparison helps to highlight the points of departure and improvisation ("Wave of Mutilation" is slower, for example). Even though a few songs sound somewhat "phoned in", with "Monkey Gone to Heaven" as an obvious example, there are a number of renditions that make you want to run around flapping your arms like a chicken - "Broken Face" and "Isla De Encanta" chug with all the power of a speeding train. Their incredible sensibilities for pop rock are on full display in "U-Mass", "Dig For Fire" and "Allison". With so much obvious talent compressed together, it's no wonder that the sheer mass of such singularity would result in the Big Bang that threw the band in all different directions. I've gone and purchased a Breeder's album (Last Splash), which I've thoroughly enjoyed - but the contrast in Kim Deal's sweet, airy melodies and Frank Black's powerful barking is an indelible loss. Even the tracks in which she provides the only vocals, such as the live version of "Into the White" on the second CD (and "Bone Machine" on the first CD), where her voice washes over you in dreamy waves, it's the juxtaposition with Black's grounding, gravelly contribution elsewhere on the album that makes it like apples of gold in settings of silver.

With so much obvious talent compressed together, it's no wonder that the sheer mass of such singularity would result in the Big Bang that threw the band in all different directions. I've gone and purchased a Breeder's album (Last Splash), which I've thoroughly enjoyed - but the contrast in Kim Deal's sweet, airy melodies and Frank Black's powerful barking is an indelible loss. Even the tracks in which she provides the only vocals, such as the live version of "Into the White" on the second CD (and "Bone Machine" on the first CD), where her voice washes over you in dreamy waves, it's the juxtaposition with Black's grounding, gravelly contribution elsewhere on the album that makes it like apples of gold in settings of silver.There are some tracks I wish would have been included, of course - "Alec Eiffel", "Hey", "Is She Weird?" and "Letter to Memphis" stand out in their absence (for me, anyway). But in the end, this is the reason "Best of" albums are such a good idea - it makes me want to slowly begin buying back the albums I've since destroyed or given away.

Wednesday, January 17, 2007

A Few Antitheses on Same Sex Relationships

Having enjoyed Kim Fabricius' continuing propositions series at Faith and Theology, I was excited to see him recently address the issue of homosexuality in the Church. Same-sex relationships, of course, remain one of the most divisive issues in Christendom (as demonstrated by the gaining fissures within Anglican Communion), producing far more heat than light on all sides of the debate. Given such an atmosphere of off-putting rhetoric, any salient theological insight should be received with gratitude, and I'm thankful for Kim's efforts to crystallize the deeper issues which concern both the ancient voices and those of contemporary dissent.

Having enjoyed Kim Fabricius' continuing propositions series at Faith and Theology, I was excited to see him recently address the issue of homosexuality in the Church. Same-sex relationships, of course, remain one of the most divisive issues in Christendom (as demonstrated by the gaining fissures within Anglican Communion), producing far more heat than light on all sides of the debate. Given such an atmosphere of off-putting rhetoric, any salient theological insight should be received with gratitude, and I'm thankful for Kim's efforts to crystallize the deeper issues which concern both the ancient voices and those of contemporary dissent.Antithesis #1 Kim addresses the nature/nurture issue in proposition 2, and provides what I think is the bedrock for an inclusivist case - namely, that homosexuality is about identity, not a set of practices or learned behavior. It's at this point where the discussion can get unnecessarily bogged down in scientific analysis about genetic predisposition - but one has to ask whether the "natural" can provide much help for Christians who are discussing the normativity of certain behaviors. Demonstrating that a behavior is "natural" requires further distinction (both in contemporary discussion and the use of Biblical arguments from "nature"), since Christian ontology is a complex of two elements - namely, the divinely stamped image of God and the fall of man into sin. All sorts of activities can also be shown with confidence to be genetically predisposed, yet Christians passionately affirm them as defective of the image God, not representative of it. Describing homosexuality as a congenital disposition, then, merely restates the debate, not advances it.

Antithesis #2 The use of the Bible in resolving these sorts of questions has been an axiomatic problem for theologians, for which homosexuality is a banner example. But Kim doesn't resort to the common tactics of simply dismissing the Bible on the grounds of interpretive impossibility - he actually acknowledges (in proposition 3) that the Bible clearly prohibits homosexuality. His real objection in appealing to Biblical authority is that it's not exactly clear whether the phenomena the Bible condemns is actually the same phenomena as is currently conceived. But this tabling of the Scriptures on the topic may be premature, on two fronts. The first is what seems to me to be an undervaluing of the sophistication of Greek sexuality. Kim's point about the difference between ancient and modern conceptions of same-sex love seems to assume the reduction of homosexual behavior to cult prostitution or episodic erotic encounters. But a few biblical scholars (and not a few classicists) acknowledge the warm, loving, and committed variety of ancient same-sex relationships. Kim is right to assume that the issue of identity bound up with homosexuality is much more pointed today than in ancient times, where activity and identity were conflated - but its important to note that these notions weren't pit against one another. Identifying oneself as "homosexual" would have certainly been foreign to Greek ears - but the "natural" attachment to the same sex celebrated by the ancients doesn't seem too far from our understanding of homosexuality (and much closer to Paul's than some are willing to admit).

Secondly, though, the Bible's teaching on sexuality goes far beyond apophatic pronouncements and prohibitions. The positive teaching of Scripture gives a theologically nuanced affirmation of heterosexuality, out of which these prohibitions grow. Jesus' teaching about man as male and female, mysteriously fused together in marriage is God's institution of a normative social convention. The imagery projected by this union is explained by Paul as the mystery of Christ's love for the Church. Far from being one metaphor one could choose among many, this is a "mystery" - the same word used in Ephesians to describe the amazing union of Jew with Gentile in the dissolution of national ethnic barriers in the Church. The Biblical language of idolatry as a diversion from this monogamous heterosexual union isn't incidental. Both adultery (Ezk. 16) and homosexuality (Ro. 1) illustrate idolatry and corrupt this intended projection. Exactly how all of this works, as Paul says in Eph. 5:32, is a mystery. But what remains clear is that he is "speaking with reference to Christ and the Church". If these connections to the imago Dei were ad hoc constructions of the later church, I might agree with Kim about the exegetical difficulty of Gen. 1:26-28 as a proof-text - but as it is, the Biblical writers themselves have seen the sexual prohibitions as having grown out of God's ideal design. It's a fundamental misunderstanding of Romans 1 to see the listing of homosexuality as just another Jewish polemic against Gentiles, or as just another sin which emerges from idolatry. Same sex relationships are given a par excellence place in his argument against idolatry because it pictures the replacement of the Other - God - for that which is the same - created things (a very Barthian critique).

Secondly, though, the Bible's teaching on sexuality goes far beyond apophatic pronouncements and prohibitions. The positive teaching of Scripture gives a theologically nuanced affirmation of heterosexuality, out of which these prohibitions grow. Jesus' teaching about man as male and female, mysteriously fused together in marriage is God's institution of a normative social convention. The imagery projected by this union is explained by Paul as the mystery of Christ's love for the Church. Far from being one metaphor one could choose among many, this is a "mystery" - the same word used in Ephesians to describe the amazing union of Jew with Gentile in the dissolution of national ethnic barriers in the Church. The Biblical language of idolatry as a diversion from this monogamous heterosexual union isn't incidental. Both adultery (Ezk. 16) and homosexuality (Ro. 1) illustrate idolatry and corrupt this intended projection. Exactly how all of this works, as Paul says in Eph. 5:32, is a mystery. But what remains clear is that he is "speaking with reference to Christ and the Church". If these connections to the imago Dei were ad hoc constructions of the later church, I might agree with Kim about the exegetical difficulty of Gen. 1:26-28 as a proof-text - but as it is, the Biblical writers themselves have seen the sexual prohibitions as having grown out of God's ideal design. It's a fundamental misunderstanding of Romans 1 to see the listing of homosexuality as just another Jewish polemic against Gentiles, or as just another sin which emerges from idolatry. Same sex relationships are given a par excellence place in his argument against idolatry because it pictures the replacement of the Other - God - for that which is the same - created things (a very Barthian critique).Antithesis #3 Kim appeals to a trajectory principle to marshal Biblical warrant for the inclusion of practicing homosexuals in the Church - an approach with as conservative prestige as to attI. Howard Marshall and William Webb. But this is a controversial concept, to be sure. Kevin Vanhoozer has aptly warned, "One problem with this approach is that the interpreter has to assume that he or she is standing at the end of the trajectory, or at least further along (or better at plotting line slope intercept formulas!) than some of the biblical authors in order to see where it leads." Again, this is a very Barthian concern, in that it puts the interpreter in His place, in the driver's seat of the redemptive-historical train. At best elusive, and at worst prejudicial, the trajectory approach toward inclusion is capable of casting nets wider than anyone might wish, depending on the judgment of the one who happens to be "plotting the slope".

Antithesis #4 I hesitate to add to Kim's eloquent call to live in the truth and witness to Christ in proposition 12. It is a beautifully stated fact of Christ existence, namely our reliance on the Spirit for words and actions tempered with love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control. Yet, in the context of the Churchly warring over this issue, it should probably be said that no one has the corner on this particular market. Not so much an antithesis as a clarification, it should be said that for those who see homosexuality as fundamentally unbiblical, there is a vast difference between our view of the morality of homosexuality and our view of the Church's moral obligations to homosexuals. That is to say that the warmth of contact and fellowship of Spirit-filled Christians with lesbian and gay people can be a reality for those who, despite their views on homosexuality as sinful, take very seriously their ethical responsibilities toward these commonly mistreated individuals. If there is any hint of antithesis here, it's at the notion that inclusion be defined in terms of a coupling of divine grace and ecclesial ontology with the moral acceptance of homosexuality - which is an all too infrequently mentioned bully tactic.

Antithesis #4 I hesitate to add to Kim's eloquent call to live in the truth and witness to Christ in proposition 12. It is a beautifully stated fact of Christ existence, namely our reliance on the Spirit for words and actions tempered with love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control. Yet, in the context of the Churchly warring over this issue, it should probably be said that no one has the corner on this particular market. Not so much an antithesis as a clarification, it should be said that for those who see homosexuality as fundamentally unbiblical, there is a vast difference between our view of the morality of homosexuality and our view of the Church's moral obligations to homosexuals. That is to say that the warmth of contact and fellowship of Spirit-filled Christians with lesbian and gay people can be a reality for those who, despite their views on homosexuality as sinful, take very seriously their ethical responsibilities toward these commonly mistreated individuals. If there is any hint of antithesis here, it's at the notion that inclusion be defined in terms of a coupling of divine grace and ecclesial ontology with the moral acceptance of homosexuality - which is an all too infrequently mentioned bully tactic.Remarkably, though, Kim Fabricius has managed to contribute to the Church's wrestling with these explosive issues without resorting to anything like the tactics he decries, delivering with the same characteristic grace and insight as we have come to expect from him.

Sunday, January 07, 2007

War of the Words

One of the hallmarks of evangelical Christianspeak is a term upon which our patron saint, Billy Graham, has built his career - it's the word "saved". You might recognize its usage in popular phrases such as, "Are ya SAVED tonight?", "When did you get saved?" and (my favorite) "That guy needs to get saved". It is, in fact, such a ubiquitous stand-in for describing evangelical Christians that a satirical movie by Brian Dannelly could lampoon us (rather successfully) under that simple monosyllabic banner. To be a Christian is to have been "saved". The more doctrinally fastidious would be quick to point out all of the corresponding components to that past event, to be sure - namely, present sanctification and future glorification; but generally salvation should be regarded as a past-tense fact. Sanctification is a term that belongs to the outworking of that past fact, and glorification is a term that belongs to the consummation of it.

One of the hallmarks of evangelical Christianspeak is a term upon which our patron saint, Billy Graham, has built his career - it's the word "saved". You might recognize its usage in popular phrases such as, "Are ya SAVED tonight?", "When did you get saved?" and (my favorite) "That guy needs to get saved". It is, in fact, such a ubiquitous stand-in for describing evangelical Christians that a satirical movie by Brian Dannelly could lampoon us (rather successfully) under that simple monosyllabic banner. To be a Christian is to have been "saved". The more doctrinally fastidious would be quick to point out all of the corresponding components to that past event, to be sure - namely, present sanctification and future glorification; but generally salvation should be regarded as a past-tense fact. Sanctification is a term that belongs to the outworking of that past fact, and glorification is a term that belongs to the consummation of it.It might strike you as strange, then, that in comparison with today's evangelical terminology that the word "saved" is in considerably modest circulation within the pages of the New Testament. Not only is this the case, but to the chagrin of the more dogmatically inclined, the salvation terminology of the Bible doesn't comport with the rigidly chronological categorization everyone is so familiar with (justification, sanctification, glorification). In fact, the Biblical word "salvation" speaks primarily not of a past event, but a (certain and secure) future hope (cf. Mt. 10:22, Ro. 13:11, 2 Tim. 2:10, Heb. 9:28, 1 Pet. 1:9). The lesson here is that theologians, even very good theologians, use Biblical words differently than the Bible uses that same terminology. This isn't because they're doing something evil or underhanded, but because they are trying to draw together all of the diverse strands of Scripture into one discernible whole - and that can be very helpful. But if people don't understand that the Biblical writers themselves didn't mean exactly the same thing these theologians mean by these words, it can result in confusion - and even more often that that, contention.

Before listing some passages to prove that point, though, it's important to notice that the Biblical passages which contain those words most familiar to systematic theology - words like justification, sanctification, adoption, regeneration, etc. - are not the only passages in the Bible which speak to those theological topics. Justification, for instance, deals with concepts of judgment, wrath, righteousness, law and covenant. Studying about justification, then, means more than just looking up every time the word shows up in the Bible. It means rooting out the concepts attached to that word. But more to the point, once you do find all the occurrences of these words, you need to know that they aren't even used the same way in every passage. The word "sanctification", for example, doesn't mean the same thing in 1 Co. 6:11 as it does in 1 Co. 7:14. That's an incredibly important point. It means that not only do theological words (like justification, sanctification and glorification) not mean the same thing in the Bible as they do in systematic theology - but they don't always mean the same thing even in the Bible itself.

Before listing some passages to prove that point, though, it's important to notice that the Biblical passages which contain those words most familiar to systematic theology - words like justification, sanctification, adoption, regeneration, etc. - are not the only passages in the Bible which speak to those theological topics. Justification, for instance, deals with concepts of judgment, wrath, righteousness, law and covenant. Studying about justification, then, means more than just looking up every time the word shows up in the Bible. It means rooting out the concepts attached to that word. But more to the point, once you do find all the occurrences of these words, you need to know that they aren't even used the same way in every passage. The word "sanctification", for example, doesn't mean the same thing in 1 Co. 6:11 as it does in 1 Co. 7:14. That's an incredibly important point. It means that not only do theological words (like justification, sanctification and glorification) not mean the same thing in the Bible as they do in systematic theology - but they don't always mean the same thing even in the Bible itself.With those caveats out of the way, and getting back to the issue at hand, once you begin looking up words like "salvation", "justification" and even "glorification", the time line mentioned above unravels. In fact, every term used by systematic theologians to describe our salvation - all of them - have an “already—not yet” pattern. Whatever saving activity is being described, it is generally (and variously) presented as beginning at a point in time, carried through the present and brought to final fulfillment or realization at the end.

Salvation is past (Eph. 2:8), present (1 Co. 1:18) and future (Mat. 10:22).

Redemption is past (1 Pet. 1:18), present (Col. 1:14) and future (Eph. 4:30).

Regeneration is past (Titus 3:5) and future (Mat. 19:28, Rev. 21:5).

Forgiveness is past (Jn. 20:23), present (1 Jn. 1:9) and future (Mt. 18:34-35).

Adoption is past (Eph. 1:5) and future (Ro. 8:23).

Justification is past (Ro. 5:11), present (Ro. 6:7 - "freed"= lit. justified) and future (Mt. 12:37).

Sanctification is past (1 Co. 6:11), present (Ro. 6:22) and future (1 Thess 5:23 - see also 2 Thess. 2:13).

Glorification is past (Ro. 8:30, i.e. proleptically), present (1 Pet. 1:8) and future (2 Thess. 1:10-12).

Much carnage has resulted among Christians because of the fundamental failure to ask what someone means by the words they're using. So the next time the theologically meticulous and doctrinaire among us (yeah, I'm included) are tempted to take someone to task for their theological imprecision, we can ask ourselves whether it's wise to indict the New Testament writers along with them.

Much carnage has resulted among Christians because of the fundamental failure to ask what someone means by the words they're using. So the next time the theologically meticulous and doctrinaire among us (yeah, I'm included) are tempted to take someone to task for their theological imprecision, we can ask ourselves whether it's wise to indict the New Testament writers along with them.