I recently enjoyed reading Stephen Bush’s proposal for a middle-way “between Hauerwas and Constantine” (what he calls “a stereoscopic political theology”, as opposed to the “monosocopic” vision of those who see the church as the only legitimate political enterprise). Bush’s paper did a wonderful job of giving expression to the gastronomic tension which has characterized my contact with the “radical orthodoxy” of neo-traditionalism. The initial enchantment that comes from beholding the magnificent, towering ideology of Yoder’s ecclesiology soon plummets into saddened disbelief at the church that actually exists in our world today. When one’s eyes are open to the extent to which powers and principalities dominate the institutional realities where we live and minister, a conscientious first response is to form apocalyptic communities in the desert rather than face the hopeless task of reform in the church, much less the state. But Bush perceptively points out that while we bear the ethical responsibility of picturing the coming kingdom, our hope is that Jesus will not only make things right in the world, but that he will transform the body of Christ to resemble its ideologue: “to be theologically accurate, we must start by noting that it is the eschaton that is the true political alternative to both nation-state and the church (emphasis mine).” That is to say the church doesn’t merely triumphantly mirror kingdom life in hopes of drawing sinners into our communities, we draw sinners into a shared groaning for God to bring the kingdom in which he establishes justice. Therefore our confession and transparent neediness forms the platform upon which meaningful political cooperation can occur without idolatrous culpability. With this tension between church and state eased (though not finally resolved), it is easier to see how one can act on the inevitable urge to support, pursue and endorse those public policies that manifest neighbor love while not engaging in idolatrous collaboration with alternative kingdoms; and that is a freeing consideration. Christian virtue is free to act outside of the singular desire to simply display Christian virtue – acts of justice, kindness and sacrificial charity can be conducted without fear of distorting ideological baggage being inadvertently attached to such actions. In other words, the desire to communicate Christian ideology doesn’t trump the actual enactment of that ideology for the benefit of those served by it. As far as I understand, Bush isn’t endorsing the Constantinian compromise to effect structural change under detached moral principles for the benefit of all – rather, he’s pointing out the moral responsibility of those who have the power to act justly to act justly even if their actions may not be construed as acts of biblical faithfulness. This, of course, doesn’t collapse the distinctions between the moral pursuits of the church versus those of the state. The church must take special care to not compromise its message in order “to help people”, not least by refusing to divorce its pursuit of particular policies from the storied ethics that drive our concern; but on the other hand we should take seriously the moral responsibility of being de-facto constituents of a participatory (albeit pagan) system.

9 comments:

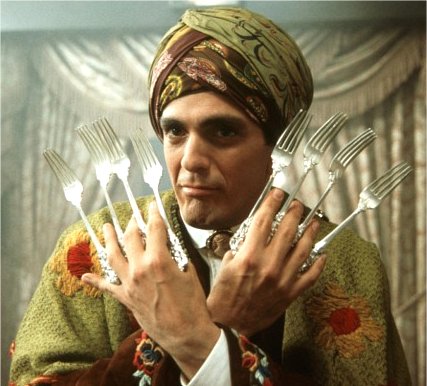

I don't understand. Maybe a chart . . .

They say that in theory there isn't much difference between theory and practice.. but in practice there is.

And in case you have never run across Wm Barcley's article.. "Apocalpytic COmmunity"

http://www.nextreformation.com/html/general/apocalyptic.htm

Thanks for the article reference, Len!

Hey, brother...I agree with you that we need to avoid Qumran’s tack on the Kingdom of God. I’m also somewhat reticent to embrace wholesale Hauerwas’ counsel against the church's institutional participation in the foreign political establishment, though I can’t vouch for Bush’s portrayal of him for ignorance of most of Hauerwas’ work. I’m more familiar with Yoder, and I don’t think Yoder will yield to Bush’s criticism. In “Discipleship as Political Responsibility,” Yoder recognizes that modern governments are much “bigger” than those of New Testament times and that seeking justice through the establishment has its place for the church/Christian. He shares with Bush the conviction that the world’s and God’s justice overlap despite not being coterminous. Yoder uses “the sword” as his main criterion for discerning when it’s inappropriate for Christians to participate actively in the establishment’s politics, i.e. when action for justice implies “bearing the sword,” we should refrain. This seems a bit simplistic to me, but at least it gives some criterion for pursuing justice through the political establishment. Bush seems to me to offer no criteria at all. His argument seems tantamount to, “If a Christian can make people’s lives better using the political establishment, she has the obligation to do it, as long as she doesn’t adopt a patriolatrous civil religion. Why? Because God loves people and calls us to promote social justice.” This seems to me little different from the Constantinian evangelical trend Bush is keen to join Hauerwas et. al. in censuring. For example, Bush says he’s not calling upon Christians to inhabit positions of power within the political establishment. But what if that’s the apparent means whereby we can obtain justice? On Bush’s argument, I can’t see why we won’t find ourselves obligated to run for political office if, with our apparently capable wisdom, we foresee that our accumulating power within the foreign establishment will lead to “justice.” This seems to me what Jesus said no to in the wilderness and what the church said yes to under Constantine and in fact well before the 4th century. Bush is concerned about “the power imbalance” (p. 10) that leads to injustice. He (with just about everyone else) urges that we not lust for power or hoard dominance, but that at times we “must exercise political power to accomplish specific gains for oppressed parties” (p. 11). I assume we’ll want/desire/lust for that “power” to “accomplish” those “gains.” Why wouldn’t we, given the misery of humanity around us? Bush judges failure to intervene through the establishment to correct “the power imbalance” as “hardly consonant with the self-emptying model of life exemplified by Jesus” (p. 10). That needs some serious explaining. What is “power” in this whole line of reasoning? The problem is not how we desire power, as if the problem only emerges when our desire becomes “lust” for power. The problem is the kind of power we desire and exercise. The issue for the Christian is not simply justice, but the means whereby it is achieved, since how we change things is proper to the change itself, i.e. how we change things indicates whether we’ve actually changed anything. The question of means is nowhere addressed in Bush’s paper, and it seems to me crucial. Missing it leads him to suggest that superficial solutions (small-scale acts of mercy) to unjust lending practices do not address “the root of the problem” (p. 9), which he apparently identifies with the political structures that institutionalize the lending practices in question. But such structures are not the root of the problem. Sin is. Does that mean that we are limited to loans by local churches and the like? I don’t think so. But if we proceed on the assumption that the institutional structures behind social injustice are “the root of the problem,” we will fail in our witness to God’s Kingdom no matter how many lives we apparently improve. I think we need some well-nuanced criteria for assessing when it is appropriate for the church to assume an institutionalized role in the foreign political establishment in favor of some particular justice. These are lacking in Bush’s proposal, and I suspect that their absence paves the slippery slope to cross-denying Constantinianism. Nevertheless, Bush’s criticism of Hauerwas’ criterion of truth vs. falsehood seems appropriate, though again, some of what I’ve read of Hauerwas makes me think Bush is scarecrowing him a bit. Regardless, refusing to participate in worldly politics because they’re “false” or “illegitimate” seems misguided. Most of my brethren in Christ engage in social justice outside the establishment for all kinds of wrong/false reasons, but that doesn’t mean they should stop, or that I shouldn’t join them. Moreover, I’m afraid most of my life rests on some measure of misperceptions and lies about God and world, and that shouldn’t paralyze me either. Part of getting to know the truth – which is Jesus - is imperfect attempts at justice with the goal of getting it right. What should give us pause I think is political participation which assumes that coercing sectors of the non-Christian population by e.g. an institutionalized majority or bargaining for favor with the political elite achieves real change in the world. Such means I think Jesus and the Apostles would have judged “fleshly” and short of recognizing the Satanic source of the problem. That leaves us with lots of room for participating in the political establishment by means of e.g. preaching the Word of God, including condemning injustice like unfair lending practices in various public fora. We can also e.g. appeal for public funds to meet social needs, mobilizing the church as well as recruiting unbelievers who share our concern over a particular issue (we’ve done this with food, clothing, and medicine in Pamplona and are presently using gov’t funds in addition to our own to provide basic material needs to the poor among our body as well as others in the city). In the case of unjust lending we could e.g. approach other financial institutions and urge them to provide an alternative to the existing, unfair practices (e.g. this sort of thing produced “the ethical bank” movement…a good, though less lucrative, place to keep your savings account if you’re concerned about profit-driven lending practices). But when we begin to believe that a particular justice is worth intentionally manipulating the pieces of the political power game or suppressing offenders by force, I fear we will have ceased to be holy, forsaken the spoken Word as the Christian weapon against injustice (e.g. 2 Cor. 10:3-6), and dropped our cross. In situations where such courses seem to be the only way to confront injustice, redemptive sacrifice, including that of the innocent and weak in the world, will achieve more justice, i.e. real change for the better, than mere reconfiguration of the sinful system. The criteria for Christian participation in the political establishment must express when we will have to allow injustice to apparently prevail (the same way the Just War theory must be able to show the injustice of a particular war), or I don’t see how anything about our participation will be distinctively Christian as it should be, notwithstanding Hosea, Amos, Luke, etc. Nevertheless, the polis of the church is robust enough to work within foreign powers (i.e. including the political establishment) for God’s Kingdom without being corrupted, but it will have to scrutinize wisely the means employed lest it mistake institutional structures for the root of the problem and spurn the foolishness of the cross. We are not smart enough to contemplate an injustice and simply decide that justice through the political establishment is “worth it.” The Christian calling will not yield to arithmetic (often consequentialist) concepts of justice. Our opposition is forces of darkness that are only empowered by the weapons of the flesh. Jesus must sharpen our obedience to the prophetic word of Amos, i.e. by dictating the means whereby we heed Amos' call. Bush’s proposal of the eschaton as the best political alternative is equivocal. His understanding of the eschaton is no alternative at all since we’re not there yet. We need real political alternatives for our discipleship now. I would say that the church is not an alternative to the political kingdoms of the world in the purest sense since its redemptive mission is to take place amidst other kingdoms rather than separated from them (à la the territorial sovereignty/isolation of Israel; or e.g. the church isn't supposed to have and dominate its own means of industrial production). You have to be engaged in, rather than separated from, foreign politics to get crucified. It is the eschaton’s invasion by the Spirit, following the way of the cross, that we’re after. We should never use (as Bush seems to on e.g. p. 7) the shortcomings of the church or unrealized eschatology or “empirical reality” as excuses for bypassing the church, or worse, engaging in unchristian politics. There is always a Christian, ecclesiologically sound way forward, regardless of the failures of the past or the present entrenchment of the church in the world’s violence. Otherwise, we’re not betting on the Spirit as we should, and we're reinforcing the church’s bankruptcy rather than remedying it. However fragmentary the church's present embodiment of God's Kingdom, and here I agree with your post, we must seek to reinvest in it, and call it back to its full-fledged redemptive mission in the world, whether its form is Emergent or Neuhausian. The apostles were a sorry lot of Kingdom ambassadors, and yet Jesus kept getting out of bed, day after day, to invest in them, to bet on God’s ability to use them. No one attempting to serve Christ as Lord should be written off.

Sounds kind of painful . . .

Painful how, Matt?

Thanks for an insightful post (as usual), Tommy! You should really think about taking advantage of my invite and posting a precis in the main page! ;)

By the way, I'm DESTROYED that I won't be able to see you at ETS/SBL/AAR this year. I just can't afford it. It sounds like it'll be a wonderful time of fellowship and vein-pulsating conversations!

blueraja, I hope you took a moment to read my response on Fide-o. There was a major miscommunication between what I meant and what you thougth I meant.

Sharad,

I just read through this and it really s-t-r-e-t-c-h-e-d my mind! ...Now why don't you write about something simple, like ... the Trinity ... or God's Omnipresence? :~) I'm looking forward to your part 2 on disunity.

Post a Comment