Believe it or not, I honestly couldn't tell at first. I was equally attracted to both of them.

. . . is a blog. In other words, a it's thinly veiled attempt to render a false sense of importance to my own unremarkable thoughts. In this case, those thoughts are primarily about Christian theology, culture and mission.

I think that postmodernism is past its sale date. It is not irrelevant, it had tremendous critical importance. However, as a pattern for future development I think it is a dead end. I think we should listen and learn from them and then move along. They have with their critique helped to clarify some of our fundamental concepts, such as culture or interpretation, but they will not last as a program in themselves. And that, the clarification and critique, changed the direction of anthropology. Therefore, my way of interpretive anthropology will go on much chastened by this. We will no longer have a simple-minded notion of what interpretation is; we are now aware of the problem of meaning-realism, and so forth. All this is terribly important. Personally, they influence me, and to some degree, I am still a part of it. As for cultural anthropology, it will in my view go on in reasonable continuity with its past.

What do you think?

This is one of the books I got for free at a publisher's reception. John Armonstrong sees this book as an important attempt to see both the human and divine facets of biblical revelatioon in thier apporpriate fullness. He generally praises the book in his review and laments the treatment it's recieved in Reformed circles. For those who may be interested, Joel Garver also wrote a review here.

This is one of the books I got for free at a publisher's reception. John Armonstrong sees this book as an important attempt to see both the human and divine facets of biblical revelatioon in thier apporpriate fullness. He generally praises the book in his review and laments the treatment it's recieved in Reformed circles. For those who may be interested, Joel Garver also wrote a review here. This is another give-away title I picked up at the conference. It looks to be typical of Packer's sanctified optimism, and for that reason alone promises to be a refreshing read. You can read David Neff's write-up on it from Christianity Today.

This is another give-away title I picked up at the conference. It looks to be typical of Packer's sanctified optimism, and for that reason alone promises to be a refreshing read. You can read David Neff's write-up on it from Christianity Today. Tom Wright whimsically commented about the horrible title afforded this treatment biblical authoirty, along with the random picture slapped on the front cover. Yet the depiction of Jesus on the front of Wright's treatment of the Bible's authority seems appropriate, since he strenuously argues for biblical revelation's dependence upon God's own authority exercised in Jesus. Here's a taste of Wright's thinking about the matter from Vox Evangelica.

Tom Wright whimsically commented about the horrible title afforded this treatment biblical authoirty, along with the random picture slapped on the front cover. Yet the depiction of Jesus on the front of Wright's treatment of the Bible's authority seems appropriate, since he strenuously argues for biblical revelation's dependence upon God's own authority exercised in Jesus. Here's a taste of Wright's thinking about the matter from Vox Evangelica. I've immensely enjoyed the other volumes of The Scripture and Hermeneutics Series, and this one looks paritcularly good with contributors like Gerald Bray, Chris Wright, James Dunn, John Webster and Charles Scobie. If Dunn's contribution is any indication of this volume's quality, I can't wait to dig in! There's a brief revew for your consideration at Beginning With Moses blog.

I've immensely enjoyed the other volumes of The Scripture and Hermeneutics Series, and this one looks paritcularly good with contributors like Gerald Bray, Chris Wright, James Dunn, John Webster and Charles Scobie. If Dunn's contribution is any indication of this volume's quality, I can't wait to dig in! There's a brief revew for your consideration at Beginning With Moses blog. Since the whole point of the series is to engender deeper understanding of the biblical text it's fitting that they focus an entire volume around the actual work of interpretation. Reading Luke, the latest offering in the series, features some first rate contributions from Anthony Thiselton, Joel Green, David Wenham, I. Howard Marshall and Max Turner. In addition to theological interpretation and issues of language, an entire division of the book is given to issues of historical reception of the Gospel.

Since the whole point of the series is to engender deeper understanding of the biblical text it's fitting that they focus an entire volume around the actual work of interpretation. Reading Luke, the latest offering in the series, features some first rate contributions from Anthony Thiselton, Joel Green, David Wenham, I. Howard Marshall and Max Turner. In addition to theological interpretation and issues of language, an entire division of the book is given to issues of historical reception of the Gospel. One of the most enjoyable sessions I attended was the panel review of this new reference volume from Baker. The criticisms included a lack of attention to historical critical issues and a leaning toward the Reformed Anglo-American contributions to the topic; but these criticisms aside, it looks like a truly majestic piece of work, and I've been looking forward to its publication for a year now. I've already perused a few articles and have enjoyed it immensely as a bedside "readers digest" of diverse theological interest. With the conference discount, this is the best 25 dollars I've spent in a while!

One of the most enjoyable sessions I attended was the panel review of this new reference volume from Baker. The criticisms included a lack of attention to historical critical issues and a leaning toward the Reformed Anglo-American contributions to the topic; but these criticisms aside, it looks like a truly majestic piece of work, and I've been looking forward to its publication for a year now. I've already perused a few articles and have enjoyed it immensely as a bedside "readers digest" of diverse theological interest. With the conference discount, this is the best 25 dollars I've spent in a while! I heard John Milbank speak at SBL and I have no idea what he's talking about. I've had my interest in Radical Orthodoxy piqued by reading Hauerwas and Yoder, but thus far I've never encountered its British roots. In attempting to read this book on the plane back to Idaho I felt as though i'd been dropped into the middle of a debate I didn't understand. All that to say I think I may pick up Smith's other volume on the topic to get some idea as to what's going on, but until then I'll have to take this one slow with a broadband connection close by so that I can look up all of the unfamiliar nomenclature.

I heard John Milbank speak at SBL and I have no idea what he's talking about. I've had my interest in Radical Orthodoxy piqued by reading Hauerwas and Yoder, but thus far I've never encountered its British roots. In attempting to read this book on the plane back to Idaho I felt as though i'd been dropped into the middle of a debate I didn't understand. All that to say I think I may pick up Smith's other volume on the topic to get some idea as to what's going on, but until then I'll have to take this one slow with a broadband connection close by so that I can look up all of the unfamiliar nomenclature. I've already read much of this book and was enthralled by the colorful and coherent picture Hays paints here. Using the categories of community, cross and new creation Hays masterfully draws a unified thread from the tapestry of New Testament witnesses. For a less than glowing appraisal, see Dale Martin's review; but for a more evenhanded treatment, see Mark Goodacre and Gilbert Meilaender.

I've already read much of this book and was enthralled by the colorful and coherent picture Hays paints here. Using the categories of community, cross and new creation Hays masterfully draws a unified thread from the tapestry of New Testament witnesses. For a less than glowing appraisal, see Dale Martin's review; but for a more evenhanded treatment, see Mark Goodacre and Gilbert Meilaender.

1) Epistemology: In just about every session I attended, the issue of epistemology lingered around the edges of the paper, only to come periodically crashing to the center, especially when dissent was expressed by panelists or audience members. When it comes to theological discourse, it seems increasingly the case that Jerusalem has actually been relocated to Athens. Issues of prolegomena and theological method have become hot-button topics in Biblical studies, and in many ways I see this as a positive development: Evangelicals are now being forced to lay their philosophical cards out on the table and expose their epistemological underwear. This kind of methodological strip-poker is the necessary beginning for any meaningful rapprochement in that it must be acknowledged that the correspondence theory of truth, accounts of epistemic justification, and traditional theories of language can neither be found in the pages of Scripture nor referenced as “obvious” common sense. Being forced to defend these notions in all of their philosophical technicalities highlights just how NOT common sense the issues really are.

1) Epistemology: In just about every session I attended, the issue of epistemology lingered around the edges of the paper, only to come periodically crashing to the center, especially when dissent was expressed by panelists or audience members. When it comes to theological discourse, it seems increasingly the case that Jerusalem has actually been relocated to Athens. Issues of prolegomena and theological method have become hot-button topics in Biblical studies, and in many ways I see this as a positive development: Evangelicals are now being forced to lay their philosophical cards out on the table and expose their epistemological underwear. This kind of methodological strip-poker is the necessary beginning for any meaningful rapprochement in that it must be acknowledged that the correspondence theory of truth, accounts of epistemic justification, and traditional theories of language can neither be found in the pages of Scripture nor referenced as “obvious” common sense. Being forced to defend these notions in all of their philosophical technicalities highlights just how NOT common sense the issues really are. 2) Postmodernism: The buzzwords in greatest currency at all of the sessions I attended were terms related to postmodernism - postfoundationalism, poststructuralism, postcolonialism, postconservativism and the like. The fact is, whether one likes it or not, the contours of contemporary debate in most of the disciplines within the guild of Biblical studies (including theology, hermeneutics and missiology) is being shaped by the variegated challenges of postmodernism. The positive effect of this has been the chastisement of positivistic excess and the cultural hegemony exercised by these disciplines under the guise of rational purity and detached objectivity (and hence the increasing discussions of prolegomena mentioned above). Yet, the negative effect is that since postmodernism tends to be more of a critique than a positive contribution, the void left by such criticisms tends to be filled by an untenable skepticism which seems incompatible with the missional prerogatives of the Church. Most of the friendly wrangling with my pals at the conference was over these sorts of issues, but the tension remains - how does one appropriate the global criticism of postmodernism, and the potential it holds for subverting the traditional impasses of Biblical studies, without resorting to nihilistic incredulity? Fortunately some positive contributions have been made in light of postmodern: Though Vanhoozer mentioned that he was "cooling" to speech-act theory as a panacea for all theological ills, I still think it represents heuristic value for textual meaning; Reformed epistemology holds some promise for an account of theological knowledge (while Bruce Marshall attempts a different account by way of a semantic conception of truth ala Alfred Tarski); critical realism is, if not rigidly methodological, at the very least an attitudinal middle-way between positivism and skepticism; Barth has proven to be a resource for a theological account of our knowledge of God, the Bible, and the (in)adequacy of human language, etc. As for the lasting value of these and other proposals, time will tell.

2) Postmodernism: The buzzwords in greatest currency at all of the sessions I attended were terms related to postmodernism - postfoundationalism, poststructuralism, postcolonialism, postconservativism and the like. The fact is, whether one likes it or not, the contours of contemporary debate in most of the disciplines within the guild of Biblical studies (including theology, hermeneutics and missiology) is being shaped by the variegated challenges of postmodernism. The positive effect of this has been the chastisement of positivistic excess and the cultural hegemony exercised by these disciplines under the guise of rational purity and detached objectivity (and hence the increasing discussions of prolegomena mentioned above). Yet, the negative effect is that since postmodernism tends to be more of a critique than a positive contribution, the void left by such criticisms tends to be filled by an untenable skepticism which seems incompatible with the missional prerogatives of the Church. Most of the friendly wrangling with my pals at the conference was over these sorts of issues, but the tension remains - how does one appropriate the global criticism of postmodernism, and the potential it holds for subverting the traditional impasses of Biblical studies, without resorting to nihilistic incredulity? Fortunately some positive contributions have been made in light of postmodern: Though Vanhoozer mentioned that he was "cooling" to speech-act theory as a panacea for all theological ills, I still think it represents heuristic value for textual meaning; Reformed epistemology holds some promise for an account of theological knowledge (while Bruce Marshall attempts a different account by way of a semantic conception of truth ala Alfred Tarski); critical realism is, if not rigidly methodological, at the very least an attitudinal middle-way between positivism and skepticism; Barth has proven to be a resource for a theological account of our knowledge of God, the Bible, and the (in)adequacy of human language, etc. As for the lasting value of these and other proposals, time will tell. 3) Theological interpretation: There seems to be a growing interest in the Bible as a Christian book. While that sounds like a stupid thing to say, the fragmentation of Biblical studies into adversarial sub-disciplines has presented a well-recognized crisis for churchly appropriations of the Bible. Historical criticism and biblical theology emphasize development, dissent and fundamental disunity in the pages of Scripture while theologians and systematicians wrestle these particularities into submission so that Christians can meaningfully speak of one book, one Gospel. Unfortunately the tug-of-war between unity and diversity has resulted in something worse than a stalemate; it’s created a taut rope for educated clergy to trip over. But a heartening turn was felt at this year’s annual meetings with Baker Academic and Brazos Press both publishing commentary series dedicated to the theological interpretation of Scripture, as well as The Dictionary for the Theological Interpretation of Scripture, a stupendous compendium of articles related to this attempted reclamation of the Bible for the Church. Of course the Scripture and Hermeneutics Series has also attempted to grapple with the issues raised by the Bible turf wars. Concurrent with these ongoing publications is the formation of a new study group within SBL, as well as a biannual journal dedicated to the topic. Hopefully these developments, alongside burgeoning theological projects which emphasize the controls of community identification and the rule of faith, represent a return to Biblical studies as a churchly endeavor.

3) Theological interpretation: There seems to be a growing interest in the Bible as a Christian book. While that sounds like a stupid thing to say, the fragmentation of Biblical studies into adversarial sub-disciplines has presented a well-recognized crisis for churchly appropriations of the Bible. Historical criticism and biblical theology emphasize development, dissent and fundamental disunity in the pages of Scripture while theologians and systematicians wrestle these particularities into submission so that Christians can meaningfully speak of one book, one Gospel. Unfortunately the tug-of-war between unity and diversity has resulted in something worse than a stalemate; it’s created a taut rope for educated clergy to trip over. But a heartening turn was felt at this year’s annual meetings with Baker Academic and Brazos Press both publishing commentary series dedicated to the theological interpretation of Scripture, as well as The Dictionary for the Theological Interpretation of Scripture, a stupendous compendium of articles related to this attempted reclamation of the Bible for the Church. Of course the Scripture and Hermeneutics Series has also attempted to grapple with the issues raised by the Bible turf wars. Concurrent with these ongoing publications is the formation of a new study group within SBL, as well as a biannual journal dedicated to the topic. Hopefully these developments, alongside burgeoning theological projects which emphasize the controls of community identification and the rule of faith, represent a return to Biblical studies as a churchly endeavor.

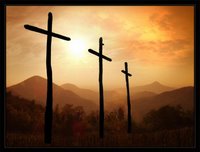

Scraping the surface of 1 Corinthians 1:10-17, it’s clear that Paul’s vision for Oneness among the redeemed community is of desperate importance. But as one continues through the chapter what becomes even clearer is his contempt for its disruption. Paul’s tone in 1 Corinthians sanctifies sarcasm in legitimate moral outrage. The pinnacle of the apostle’s rhetorical razing comes in 4:7-8 – but its precursor shows up as early as his very first paragraph. Verses 13-17 read, “Has Christ been divided? Paul was not crucified for you, was he? Or were you baptized in the name of Paul? 14 I thank God that I baptized none of you except Crispus and Gaius, 15 so that no one would say you were baptized in my name. 16 Now I did baptize also the household of Stephanas; beyond that, I do not know whether I baptized any other. 17 For Christ did not send me to baptize, but to preach the gospel, not in cleverness of speech, so that the cross of Christ would not be made void.”

Scraping the surface of 1 Corinthians 1:10-17, it’s clear that Paul’s vision for Oneness among the redeemed community is of desperate importance. But as one continues through the chapter what becomes even clearer is his contempt for its disruption. Paul’s tone in 1 Corinthians sanctifies sarcasm in legitimate moral outrage. The pinnacle of the apostle’s rhetorical razing comes in 4:7-8 – but its precursor shows up as early as his very first paragraph. Verses 13-17 read, “Has Christ been divided? Paul was not crucified for you, was he? Or were you baptized in the name of Paul? 14 I thank God that I baptized none of you except Crispus and Gaius, 15 so that no one would say you were baptized in my name. 16 Now I did baptize also the household of Stephanas; beyond that, I do not know whether I baptized any other. 17 For Christ did not send me to baptize, but to preach the gospel, not in cleverness of speech, so that the cross of Christ would not be made void.” As much as Paul despises rhetoric for the sake of rhetoric, he masterfully baptizes it for Christian use in what’s called a “reductio ad absurdum”. This sort of argument carries your opponent’s thinking to its logical end in order show its absurdity. Parents employ this timeless classic in response to the perennial complaint, “But everyone else is doing it!” The familiar reductio ad absurdum in that case is (say it with me), “If everyone else jumped off a bridge, would you?” The force of the argument is to expose the disastrous logical implications of a particular line of thinking – and the best way to do that is with a question. In addressing the Corinthian mindset, Paul’s got three of them.

As much as Paul despises rhetoric for the sake of rhetoric, he masterfully baptizes it for Christian use in what’s called a “reductio ad absurdum”. This sort of argument carries your opponent’s thinking to its logical end in order show its absurdity. Parents employ this timeless classic in response to the perennial complaint, “But everyone else is doing it!” The familiar reductio ad absurdum in that case is (say it with me), “If everyone else jumped off a bridge, would you?” The force of the argument is to expose the disastrous logical implications of a particular line of thinking – and the best way to do that is with a question. In addressing the Corinthian mindset, Paul’s got three of them. The first is, “Has Christ been divided?” For Paul, church splitting absurdly implies that Jesus Himself can be broken into pieces and parceled out in chunks among various factions. How this follows from disunity is not easily discernable for most modern evangelicals, since Christ and the Church are typically held at arm’s length from one another. Resigned to the impossibility of moral victory and desiring to minimize the damage to Jesus’ reputation, the only available coping mechanism is to see His ministry as radically independent from that of the Church. But this is a fantasy. The Church, like it or not, is in mystical union with Jesus Christ. So much so, in fact, that 1 Co. 6:15-20 says when a believer joins himself to a prostitute, he’s not only defiling Himself – he’s defiling Jesus too. 1 Co. 12:27 puts it even more plainly – “Now you are Christ’s body, and individually members of it.” The neat distinctions we make between Christology and Ecclesiology can be worse than misleading; they can blind us from the fact that the Church is His body, and as such bear His reputation, constitute His earthly presence and mediate His ongoing ministry. As such, seeking to separate believers from one another is a direct assault on Jesus Himself because, though comprised of many members, He is one.

The first is, “Has Christ been divided?” For Paul, church splitting absurdly implies that Jesus Himself can be broken into pieces and parceled out in chunks among various factions. How this follows from disunity is not easily discernable for most modern evangelicals, since Christ and the Church are typically held at arm’s length from one another. Resigned to the impossibility of moral victory and desiring to minimize the damage to Jesus’ reputation, the only available coping mechanism is to see His ministry as radically independent from that of the Church. But this is a fantasy. The Church, like it or not, is in mystical union with Jesus Christ. So much so, in fact, that 1 Co. 6:15-20 says when a believer joins himself to a prostitute, he’s not only defiling Himself – he’s defiling Jesus too. 1 Co. 12:27 puts it even more plainly – “Now you are Christ’s body, and individually members of it.” The neat distinctions we make between Christology and Ecclesiology can be worse than misleading; they can blind us from the fact that the Church is His body, and as such bear His reputation, constitute His earthly presence and mediate His ongoing ministry. As such, seeking to separate believers from one another is a direct assault on Jesus Himself because, though comprised of many members, He is one. This first question reveals an absurdity in their view of Christ’s Person; the second question exposes the absurdity in relationship to Christ’s work. Even though he used his own name, he could have just as easily inserted the names of Apollos or Peter – none of these men died on your behalf – so why are you choosing sides according to your loyalty to them? I think we should feel free to read the names of any respected teacher in the Church, past or present in verse 13. Is this where the lines that divide us should be drawn? Should we be organizing ourselves according to these sorts of loyalties? Paul’s answer was plainly, “Hell no.” And the reason for that is because of the nature of Christ’s work on the cross – it demands exclusive loyalty. Neither John Calvin, Charles Spurgeon nor John Wesley died for our sins. Neither John MacArthur nor Rick Warren reconciled our rebellious hearts to God. And since it was none other than Jesus who did that, there is no other loyalty which should be used as the acid test of Christian fellowship. The oft-repeated ultimatum, “Do you stand with X or do you stand with Y” exemplifies Satanic brilliance, because regardless of which option we choose, we’ve inadvertently hacking the heart of true discipleship: exclusive loyalty to Jesus Christ.

This first question reveals an absurdity in their view of Christ’s Person; the second question exposes the absurdity in relationship to Christ’s work. Even though he used his own name, he could have just as easily inserted the names of Apollos or Peter – none of these men died on your behalf – so why are you choosing sides according to your loyalty to them? I think we should feel free to read the names of any respected teacher in the Church, past or present in verse 13. Is this where the lines that divide us should be drawn? Should we be organizing ourselves according to these sorts of loyalties? Paul’s answer was plainly, “Hell no.” And the reason for that is because of the nature of Christ’s work on the cross – it demands exclusive loyalty. Neither John Calvin, Charles Spurgeon nor John Wesley died for our sins. Neither John MacArthur nor Rick Warren reconciled our rebellious hearts to God. And since it was none other than Jesus who did that, there is no other loyalty which should be used as the acid test of Christian fellowship. The oft-repeated ultimatum, “Do you stand with X or do you stand with Y” exemplifies Satanic brilliance, because regardless of which option we choose, we’ve inadvertently hacking the heart of true discipleship: exclusive loyalty to Jesus Christ. On top of these implications Paul piles on one more absurdity – “Or were you baptized in the name of Paul?” These divisions reflected different spiritual heritages, the products of different discipleship. Some were influenced more by Peter, others by Apollos; some were the products of Paul’s teaching, and still others claimed to be purists, relying only on the words of Jesus Himself. Surely, then, these divisions reflected different faiths! Not so. No matter who their spiritual fathers were, every single believer in the Corinthian community, as well as every single believer in Macedonia, the Empire, in both times past and present were all baptized into the same name: that of King Jesus. And that baptism was based not on receiving the good news about Paul, Peter or Apollos, but about Jesus, who God has made Lord and Christ by virtue of His death and resurrection. The message of the cross was the basis for baptism in the name of Jesus, and therefore dividing the fellowship was a way of emptying the cross of its significance. The cross brings men of every tribe, tongue and nation into one body through baptism. Gal. 3:28 says, “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free man, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus.”

On top of these implications Paul piles on one more absurdity – “Or were you baptized in the name of Paul?” These divisions reflected different spiritual heritages, the products of different discipleship. Some were influenced more by Peter, others by Apollos; some were the products of Paul’s teaching, and still others claimed to be purists, relying only on the words of Jesus Himself. Surely, then, these divisions reflected different faiths! Not so. No matter who their spiritual fathers were, every single believer in the Corinthian community, as well as every single believer in Macedonia, the Empire, in both times past and present were all baptized into the same name: that of King Jesus. And that baptism was based not on receiving the good news about Paul, Peter or Apollos, but about Jesus, who God has made Lord and Christ by virtue of His death and resurrection. The message of the cross was the basis for baptism in the name of Jesus, and therefore dividing the fellowship was a way of emptying the cross of its significance. The cross brings men of every tribe, tongue and nation into one body through baptism. Gal. 3:28 says, “There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free man, there is neither male nor female; for you are all one in Christ Jesus.”“It is easy to see the urgency of a paragraph like this for the contemporary church, which not only often experiences quarrels such as these at the local level, but also is deeply fragmented at every other level. We have churches and denominations, renewal movements that all too often are broken off and become their own “church of Christ,” and every imaginable individualistic movement and sect. Even in a day of various kinds of ecumenism, the likelihood of total visible unity in the church is more remote than ever. This fragmentation is both a shame on our house and a cause for deep repentance. If there is a way forward, it probably lies less in structures and more in our readiness to recapture Paul’s focus here – on the preaching of the cross as the great divine contradiction to our merely human ways of doing things.”