Saturday, December 31, 2005

Monday, December 26, 2005

Biblical Potpourri for 500 . . .

The study of the Bible is an inherently political action, in more ways than one. There are, of course, the oft noted ways in which this is so, such as the way reading the Bible establishes the relationship between Church and world in public life; but there are more intramural ways in which reading the Bible is a poltically charged endeavor, and I'm not talking about denominationalism. A good deal of commotion is generated in what one could call "departmentalism".

The study of the Bible is an inherently political action, in more ways than one. There are, of course, the oft noted ways in which this is so, such as the way reading the Bible establishes the relationship between Church and world in public life; but there are more intramural ways in which reading the Bible is a poltically charged endeavor, and I'm not talking about denominationalism. A good deal of commotion is generated in what one could call "departmentalism".It seems like studying the Bible in an academic setting means being swallowed whole by colonizing sub-disciplines, all of which vie for supremacy among specialists. The net effect of hyper-specialization is that not only is a pastor (such as myself) beset with choices between different translations of Scripture, and choices of interpretations within the text of Scripture, and choices of hermeneutical schemes to interpret Scripture, and choices of theological systems that are faithful to Scripture, but with the choice of which one of these questions is more important than the others! Which questions are most determinative in trying to understand, preach and obey the Bible?

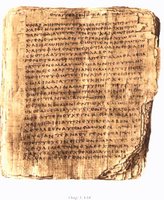

Bart D. Ehrman argues that textual criticism is every bit as ideological as it is textual - how can a person even begin to engage in "biblical theology" if the selection of texts which supposedly constitute an author's (or set of editors') "theology" is arbitrarily selected by contemporary scholarship? The theological nature of variant readings mean that in selecting what is supposedly the "original" text one is ultimately aligning herself with competing theologies. How can Scripture be said to be inspired if we don't even know which words belong to Scripture? How reliable are the manuscripts which make up the Bible? How substantive were the changes and is the original text recoverable? Even if it does make sense to speak of an "autograph", what does the fact of scribal changes say about the cohesiveness of Christianity in its earliest days? Moreover, if one can't establish an authoritative text, what's the point of doing theology or talking about interpretation?

Bart D. Ehrman argues that textual criticism is every bit as ideological as it is textual - how can a person even begin to engage in "biblical theology" if the selection of texts which supposedly constitute an author's (or set of editors') "theology" is arbitrarily selected by contemporary scholarship? The theological nature of variant readings mean that in selecting what is supposedly the "original" text one is ultimately aligning herself with competing theologies. How can Scripture be said to be inspired if we don't even know which words belong to Scripture? How reliable are the manuscripts which make up the Bible? How substantive were the changes and is the original text recoverable? Even if it does make sense to speak of an "autograph", what does the fact of scribal changes say about the cohesiveness of Christianity in its earliest days? Moreover, if one can't establish an authoritative text, what's the point of doing theology or talking about interpretation?Biblical theology is an enterprise that is notoriously spoken of as "in crisis" even though it continues to pulse with activity. While the Biblical Theology Movement can said to have been leveled by the criticisms of James Barr and company, the academic task of establishing a plausiblly historically situated theology continues. Moreover the basic project of Biblical theology seems an invioble part of Biblical studies as a whole. Baruch Spinoza or J.P. Gabler didn't invent the concern that the Bible should speak for itself, with its own categories and agendas. The idea that the Bible should be understood on its own terms instead of serving as a dogmatic diving board is something close to a universal intuition. It's this inutition that makes the discipline of Biblical theology an invetibly colonizing force on other disciplines, ready to slap the hands of the ambitious systematician, reprove the anachronisitic philosophical categories of the hermeneutically fanciful and carry the banner of Biblical authority for the Church.

On the other hand, without dogmatics it becomes unclear what unites the cacophany of divergent voices of Scripture in all their historical particularity. What does something Isaiah said in his historical context have to do with anything Matthew might say in his? Can one even "preach the Gospel" without engaging in some kind of supra-historical creedal synthesis? For all the lofty ambitions of Biblical theology, its historical interests yield such a strict emphasis on diversity that the Bible collapses into a disjointed product of human imagination instead of the singular voice of God. But more than that, theological preunderstandings and creedal loyalty subtly (and sometimes not-so-subtly) fund both historical criticical and Biblical theological methodology; and that fact places systematics in a position of primary importance.

The new totalizing force in Biblical studies seems to be the issue of how one relates to the postmodern turn, which has brought with it a self-critical emphasis on philosophical starting points. Postmodernism seeks to pull back the curtain from our detached claims to theological knowledge, revealing the wizard of culturally informed theories of truth and justification. Epistemology has become the new prolegomena. One can't engage in any level of the theological task without giving account of the philosophical superstructures within which it takes place. I would have never imagined that being interested in Biblical studies would impel me toward the likes of Wittgenstein, Searle, Heidegger, Tarski or Davidson.

The new totalizing force in Biblical studies seems to be the issue of how one relates to the postmodern turn, which has brought with it a self-critical emphasis on philosophical starting points. Postmodernism seeks to pull back the curtain from our detached claims to theological knowledge, revealing the wizard of culturally informed theories of truth and justification. Epistemology has become the new prolegomena. One can't engage in any level of the theological task without giving account of the philosophical superstructures within which it takes place. I would have never imagined that being interested in Biblical studies would impel me toward the likes of Wittgenstein, Searle, Heidegger, Tarski or Davidson.Textual criticism, biblical theology, systematic theology and philosophy are just a few of the sub-disciplines within the guild that seem to draw all others into their orbit, defining the problems and solutions in light of their own gravitational fields.

So:

If you're in ministry, which of these disciplines do you believe is most determinative in trying to faithfully minister the Bible to your people?

If you're in the academy, does this picture misrepresent the current state of affairs?

If you're neither (or both) of the above, do you think that there's one primary "center" for theological studies, and if so what is it?

Thursday, December 15, 2005

The results are in . . .

David Palmer

My wife and I LOVE the series "24" - but for the life of me I can't figure out how I managed to be President Palmer on this quiz. Someone want to explain it to me?

Which 24 Character are you?

brought to you by Quizilla

UPDATE: Here are the results for my wife:

Kate Warner

Monday, December 12, 2005

Dig Doug?

Occasionally I get a hankering for conspicuously ornamental prose, and that's when I wander over to Doug Wilson's Blog and Mablog. While I can't always agree with him, I dig Doug's style. Of all the the white knights fighting for the claim of a truly Reformed heritage Doug seems to be one of the most reasonable and even charitable. His assessment of N.T. Wright's various contributions was a still small voice of sanity among the clamor of warrior children suiting up for battle.

Occasionally I get a hankering for conspicuously ornamental prose, and that's when I wander over to Doug Wilson's Blog and Mablog. While I can't always agree with him, I dig Doug's style. Of all the the white knights fighting for the claim of a truly Reformed heritage Doug seems to be one of the most reasonable and even charitable. His assessment of N.T. Wright's various contributions was a still small voice of sanity among the clamor of warrior children suiting up for battle.On the other hand, there are certain topics which elicit some of the most vengefully florid verbage you'll ever hear from Doug, and postmodernism happens to be one of those subjects. In a recent post he criticizes the theological moves being made by postconvservatism by making a distinction between the autonomous, secular Enlightenment varieties of foundationalism (the Cartesian variety) and dependent Christian versions of it (inerrantism). The fundamental problem with the Enlightenment project, says Wilson, isn't the existence of foundations but an ethos of selfishness. In his view, rationalism is idolatry because it assumes that objectivity and certain knowledge flows from the self while true Christianity maintains that it flows from God. The problem with postmodern criticisms, then, is that they are decrying the impossibility of objective human knowledge without advocating (or demonstrating) dependence upon God's provision of it in the Scriptures. The desire to formulate interpretive strategies which mitigate human objectivity or propositional certainty is thus seen as "modernity's nervous breakdown"; a "whimpering selfishness".

All of this isn't completely untrue - there are some ways in which postmodern theology seems to miss the irony behind discussing the complexity and impenetrability of "revelation". In what sense does it "reveal" anything? But what Doug (and a good many others) seem to miss is the very issue which postconservative theology seeks to wrestle with - and that is, of course, the hermeneutical issue. To speak of the Scriptures as an authoritative source of theology is uncontroversial among many postconservative evangelicals; the problem becomes how the Scriptures function authoritatively in light of hermeneutical (not textual) indeterminancy. The fact is that our only access to the Scriptures is through subjective medium.

All of this isn't completely untrue - there are some ways in which postmodern theology seems to miss the irony behind discussing the complexity and impenetrability of "revelation". In what sense does it "reveal" anything? But what Doug (and a good many others) seem to miss is the very issue which postconservative theology seeks to wrestle with - and that is, of course, the hermeneutical issue. To speak of the Scriptures as an authoritative source of theology is uncontroversial among many postconservative evangelicals; the problem becomes how the Scriptures function authoritatively in light of hermeneutical (not textual) indeterminancy. The fact is that our only access to the Scriptures is through subjective medium.It's hard to disagree with all of Doug's railing against both the enthroned and the chastened Self. It's equally hard to refrain from celebrating the truimph of the triune God in "de-centering" the Self as He speaks in Scripture. What remains puzzling, though, is how we can come to the Scriptures without our "selves". Does God come to the Scriptures for us, on our behalf, or must we come to hear Him speak? Is there some way to come without bringing ourselves with us? If not, how have we been "de-centered" by God? What accounts for the discrepancies between the Spirit taught theologies of Luther and Calvin, Wesley and Warfield or, for that matter, James White and Doug Wilson? Which party is being autonomous in this case? Who's doing the whoring? More importantly, how do we know, and how do we avoid it ourselves such that our theology truly represents the mind of God as revealed in Scripture? Is it possible for two people to be dependent upon the Spirit, committed to hearing Scripture's voice and not their own, both being thoroughly "de-centered by the triune God" to disagree on what Scripture says? What does all of this say for the Bible's authority?

Unfortunately the problem doesn't dissolve in rhetoric (even Wilson's mostly delightful rhetoric). The plain fact of the matter is that Spirit-filled Christians of great learning and admirable lifestyles give persuasive cases for opposing theological commitments while at the same time claiming an equal share of God's authority - and that's the best case scenario. In the worst case scenario pernicious regimes and self-serving individuals help themselves to the authority of God's Word in order to bolster their own ideologies. Claiming to "stand on God's Word" thus becomes an impenetrable bulwark of self-preservation, deceit and manipulation. That's what postmodernism seeks to expose. Postconservatives may acknowledge that God has spoken in the Scriptures and that it is authoritative; what they are wrestling with is how that works. How can our apprehension, systematization and application of Scripture can be said to represent God's mind, given the fact that we can't understand revelation apart from all of our limitations? As these brethren cast about for answers, I can't say I always agree with the positive suggestions for a way forward; but for all the hellish controversy Doug's been through (lovingly handcrafted by Presbyterians standing on the word of God), I can't see why he can't recognize some small glimmer of prophetic quality in that critique.

For all of the rhetorical panache of Wilson's closing illustration ("God tells Adam to stay away from the tree, and Adam walks over to it, whistling, telling himself that 'to pretend that he, a finite creature, was capable of understanding, still less comprehending, this voice from the numinous realm -- why, that would be the true arrogance. And gee, that fruit looks good. I believe I'll have some'), the sad fact is that one needn't craft clever parables to illustrate the abuses of Biblical authority in Western history. The examples are all too real. Is it possible to be too sqeamish about Christian collusion with Nazi Germany in the name of the Scriptural mandate to "be subject to the governing authorities"? But the problem is worse than that. It isn't just that some people do bad things with the Bible; it's that the fact that everyone claims their own interpretations as God's authoritative decree without the possibility of falsification, which of course renders any concept of authority useless. That's not to say that there's no consensus as to what the Bible says, or that it's not authoritative; but it is to say that there is plenty of conceptual work to be done in terms of how it functions authoritatively in light of these issues. To say "just read it" is more than disingenuous - it'd dangerous, because the highest form of self-exaltaion is to equate oneself to the living God and invoke His name in the advancement of falsehood. Postconservative theologies are sincere attempts to treat these issues with appropriate solemnity.

For all of the rhetorical panache of Wilson's closing illustration ("God tells Adam to stay away from the tree, and Adam walks over to it, whistling, telling himself that 'to pretend that he, a finite creature, was capable of understanding, still less comprehending, this voice from the numinous realm -- why, that would be the true arrogance. And gee, that fruit looks good. I believe I'll have some'), the sad fact is that one needn't craft clever parables to illustrate the abuses of Biblical authority in Western history. The examples are all too real. Is it possible to be too sqeamish about Christian collusion with Nazi Germany in the name of the Scriptural mandate to "be subject to the governing authorities"? But the problem is worse than that. It isn't just that some people do bad things with the Bible; it's that the fact that everyone claims their own interpretations as God's authoritative decree without the possibility of falsification, which of course renders any concept of authority useless. That's not to say that there's no consensus as to what the Bible says, or that it's not authoritative; but it is to say that there is plenty of conceptual work to be done in terms of how it functions authoritatively in light of these issues. To say "just read it" is more than disingenuous - it'd dangerous, because the highest form of self-exaltaion is to equate oneself to the living God and invoke His name in the advancement of falsehood. Postconservative theologies are sincere attempts to treat these issues with appropriate solemnity.In light of that, it may be worth asking, "has postmodernism actually influenced evangelicals to give the triune God their middle finger in the way Doug fears?"

Observe one of Doug's frequent debate partners on the topic, P. Andrew Sandlin; he has listed a few tenents which can be said to be influenced by postmodernism. Among them are the analagous way in which men apprehend God (sharp Creator-creature distinction), the ontically holistic nature of knoweldge (a being, not a mind, thinks), the fact that humans only see in partial glimpses, not exhaustively, the danger of human arrogance in ascribing one's own views to God, and the fact that our theology should be dynamic, open to change in light of Scripture. All of that sounds like a fairly "de-centered self" to me.

Sunday, December 04, 2005

Take, Eat . . .(part 2)

1 Corinthians 10, at first glance, struck me as a strange smattering of topics artifiically smashed together by someone with attention deficit disorder. Paul speaks about the children of Israel in the wilderness, and seems to want to instruct the Corinthians with their example; but then the topic of communion pops up out of nowhere in verse 17. After that he launches into the topic of food sacrificed to idols, and then communion again, and then meat sold in the marketplace, and then “doing all things for the glory of God” – what does any one of those have to do with the rest? After spending some time trying to answer that question, I think I discovered what the obstacle was, and (as usual) it was to be found less in the text than it was in me; namely, in my shallow expectations about what Church should be. I default into thinking of the church as a service; but Paul thought of it as a family that extends even beyond those now living (the children of Israel "ate spiritual food" and "drank spiritual drink"). The relevance of Israel's appetite for idolatry and the Corinthian confusion over meat sacrificed to idols are all bound together by verse 17 – when we partake of Christ together, we become family, and we are thus (verse 24) to “seek the good of one another.”

1 Corinthians 10, at first glance, struck me as a strange smattering of topics artifiically smashed together by someone with attention deficit disorder. Paul speaks about the children of Israel in the wilderness, and seems to want to instruct the Corinthians with their example; but then the topic of communion pops up out of nowhere in verse 17. After that he launches into the topic of food sacrificed to idols, and then communion again, and then meat sold in the marketplace, and then “doing all things for the glory of God” – what does any one of those have to do with the rest? After spending some time trying to answer that question, I think I discovered what the obstacle was, and (as usual) it was to be found less in the text than it was in me; namely, in my shallow expectations about what Church should be. I default into thinking of the church as a service; but Paul thought of it as a family that extends even beyond those now living (the children of Israel "ate spiritual food" and "drank spiritual drink"). The relevance of Israel's appetite for idolatry and the Corinthian confusion over meat sacrificed to idols are all bound together by verse 17 – when we partake of Christ together, we become family, and we are thus (verse 24) to “seek the good of one another.”Paul's point seems to be that recieving Christ and fleeing idols is something done by a community, not by piously introspective individuals. By recieivng Christ and fleeing idolatry we mark ourselves out as the one people of God; those who, through Christ, are to suceed where Israel failed. The issue of eating meat sacrificed to idols wasn't so much a crisis of personal morality, but a call for the Corinthians to be a distinct people from their pagan neighbors (something Israel failed to do). Yet, as verse 27 indicates, Paul's desire isn't for selfish community formation. Love is the rule, both among believers and unbelievers, which should manifest itself in a desire to protect their consciences. But in all of these things the driving concern is for the integrity of the community, marked out by communion.

The ancient world held table fellowship as one of the highest forms of friendship, intimacy and unity. This is why the issue of who Jesus chose to eat with was such a big deal to the Pharisees. The Pharisees even saw their tables at home as substitutes for the altar in the Jerusalem Temple. Their outrage at Jesus not “washing his hands” before he ate betrayed their concern for sacramental purity and community identification, not legalism or neurotic hygiene. Those who were allowed to come to the table together were defined according to ethnicity, race, class, wealth and status.

The ancient world held table fellowship as one of the highest forms of friendship, intimacy and unity. This is why the issue of who Jesus chose to eat with was such a big deal to the Pharisees. The Pharisees even saw their tables at home as substitutes for the altar in the Jerusalem Temple. Their outrage at Jesus not “washing his hands” before he ate betrayed their concern for sacramental purity and community identification, not legalism or neurotic hygiene. Those who were allowed to come to the table together were defined according to ethnicity, race, class, wealth and status.But in Jesus, Paul says, Jew and Gentile, slave and free, male and female, barbarian and Scythian all come to the same table. It’s no wonder that the early church was viewed as destructive to society; it broke down all the divisions that people thought of as necessary to keep its proper order! By eating at the Lord's Table together, the disciples were doing something revolutionary – they were reorganizing their family relationships, their friendships, and all those they would associate with not around extended relatives, common interests, shared status or level of income but around Jesus. Communion shattered societal norms of friendship and family.

The early church was just that: a family. They provided for one another; they paid one another’s debts; they ate in one another’s homes; they adopted uncared for children in one another’s families; they opened their homes and finances to one another and even called one another “brother” and “sister”. And that, believe it or not, was every bit as weird and suspicious to the Roman world as it would be for us today. For people to share in one another’s lives like that, to that degree – to not just call each other “brother” but to actually treat one another as immediate family members, was considered “unnatural” in the Roman world. But at the same time it made some people uncomfortable, it drew thousands of other people to the table, and into God’s kingdom.

When we take communion we aren’t just affirming our union with Christ in mystical fellowship; we’re affirming our union with one another as friends, but more than just acquaintances who share a common faith. We’re affirming a union that’s more like limbs to a body or the members of a family in a household. When we take of the same bread and drink of the same cup we receive the same Jesus and recognize that no one among us recieves more or less than another. 1 Co. 11:27 warns us to take this proclamation with utmost seriousness. This verse is usually used as an exhortation to "search your heart" for any moral failing that might make you unworthy of participating in communion. Sometimes a moment of silence is even provided to help you uncover any unconfessed sin that you might need to take care of before taking part. Maybe that's not a bad idea - but it has nothing to do with what Paul's actually concerned about.

Verses 20-22 give us an idea about what "unworthiness" he has in mind: “Therefore when you meet together, it is not to eat the Lord’s Supper for in your eating each one takes his own supper first; and one is hungry and another is drunk. What! Do you not have houses in which to eat and drink? Or do you despise the church of God and shame those who have nothing? What shall I say to you? Shall I praise you? In this I will not praise you.” Apparently when the Corinthians came to the Lord’s table the wealthy (those who owned homes) pushed their way to the front of the line in their debauchery and left nothing for the poor brothers among them – those who “have nothing”.

In verse 33 Paul says what he has in mind as behavior "worthy" of communion: “So then, my brethren, when you come together to eat, wait for one another.” Partaking in a worthy manner isn't an act of pious individualism; it involves honoring and loving all those who have recieved Jesus as members of the same family. The reconciliation of God's Creation, the advent of His shalom has begun in us, upon whom the "ends of the ages have come" (1 Co. 10:11), and communion signals the inbreaking of God's coming era of mutual, self-giving, Christlike love.

In verse 33 Paul says what he has in mind as behavior "worthy" of communion: “So then, my brethren, when you come together to eat, wait for one another.” Partaking in a worthy manner isn't an act of pious individualism; it involves honoring and loving all those who have recieved Jesus as members of the same family. The reconciliation of God's Creation, the advent of His shalom has begun in us, upon whom the "ends of the ages have come" (1 Co. 10:11), and communion signals the inbreaking of God's coming era of mutual, self-giving, Christlike love.Next time you receive the elements, think about what you’re about to do. You are receiving Jesus as the satisfaction of your souls, and fleeing idolatrous cravings as "that which can never satisfy". You are identifying yourself with one people of God and committing yourself to honoring the most "unseemly" of its members. Only if you believe these things can you, as it says at the end of ch. 10, “eat or drink to the glory of God”.

Friday, December 02, 2005

Take, Eat . . .(part 1)

In preparation for communion with my congregation this Sunday I thought I'd post some of my reflections from 1 Corinthians 10 on the matter:

In preparation for communion with my congregation this Sunday I thought I'd post some of my reflections from 1 Corinthians 10 on the matter:Because of our historical controversy with the Roman Catholic Church, and the subsequent Zwinglian over-reaction (adopted by most evangelical communities), the Lord’s table has become a naturalistic liturgical afterthought. In services I've attended, participated in and even led, there's always been a concerted effort to explain that nothing mystical is actually taking place, and that the entire ceremony is nothing more than an occassion for self-examination. But for Paul (and both Lutheran and Calvinistic traditions), communion wasn’t just an “ordinance” in the sense of a regulation which the church is supposed to meet in order to be “up to code”; he considered the holy meal “spiritual food” and “spiritual drink”. For all of the Reformers' sola fide conviction, for the most part they didn't seem to share the soteriological queasiness with which we repeat the words "this is my body" and "this is my blood". They affirmed with equal vigor that bread and wine can’t save anybody. They ardently protested against the idea that priests could somehow transform these elements into the actual flesh and blood of Christ by cultic incantation.

Yet, with Paul, they say communion as an act of mystical, spiritual fellowship both with Jesus and with one another. In verses 15-16 Paul declared that the cup is a means of blessing in which we share in Christ’s body and his blood. The children of Israel in the wilderness were supernaturally sustained by God not just physically, but spiritually; by the manna from heaven and the water from the rock which Moses struck. In their eating and drinking they tangibly experienced God’s deep personal commitment to delivering them from their slavery and bringing them into the new land; they were vividly reminded of their total dependence upon Him for their every provision. In eating, they entered into fellowship with God; they sat at His table. But they also entered into fellowship with one another. This dependence and salvation wasn’t just experienced by one, two or a two-hundred of them but by every single Israelite in the desert. They were delivered as a community, as a fellowship as a family. They all ate the same spiritual food and they all drank the same spiritual drink.

But notice that there was nothing automatically sanctifying about eating this meal; it didn’t automatically reconcile them to God, and it didn’t magically reconcile them to one another. In fact, Paul reminds us that even after receiving spiritual food and spiritual drink they still “craved evil things”. They weren’t satisfied by the meal God was providing; and so verse 6 says that their hunger turned to lust, and in verse 7 their lust turned to immorality, and verse 10 says that these evil cravings and all their attempts to fill it brought not contentment, not satisfaction, not full bellies, but grumbling. God was displeased with them, and he poured out His wrath upon them; but even before this there was judgment, because as they sought to satisfy their hunger with idolatry and immorality, they remained hungry, and they died in their discontentment.

But notice that there was nothing automatically sanctifying about eating this meal; it didn’t automatically reconcile them to God, and it didn’t magically reconcile them to one another. In fact, Paul reminds us that even after receiving spiritual food and spiritual drink they still “craved evil things”. They weren’t satisfied by the meal God was providing; and so verse 6 says that their hunger turned to lust, and in verse 7 their lust turned to immorality, and verse 10 says that these evil cravings and all their attempts to fill it brought not contentment, not satisfaction, not full bellies, but grumbling. God was displeased with them, and he poured out His wrath upon them; but even before this there was judgment, because as they sought to satisfy their hunger with idolatry and immorality, they remained hungry, and they died in their discontentment.The point here is that Christ is our spiritual food and spiritual drink, not just for when we were converted, not just for yesterday, but for the present, and for every moment we call “now”. He’s given to us in order to satisfy our cravings; and so this meal which we share isn’t just a law to observe; Paul says its one means by which we share in the body and blood of Christ and find continual food to sustain our spiritual lives. It’s a reminder that we must both receive Christ and flee from idols not once (at conversion), but always and “as often as you eat of it” and “as often as you drink it”. And he doesn’t say that we need to do that not by simply speaking about it. We receive these graces and proclaim His death until He comes by actually eating of the bread and drinking from the cup.

Consider this lengthy quote from Calvin as to the importance of the bread and the cup for our spiritual sustenance:

Consider this lengthy quote from Calvin as to the importance of the bread and the cup for our spiritual sustenance:“For as God, regenerating us in baptism, ingrafts us into the fellowship of his Church, and makes us his by adoption, so we have said that he performs the office of a provident parent, in continually supplying the food by which he may sustain and preserve us in the life to which he has begotten us by his word. Moreover, Christ is the only food of our soul, and, therefore, our heavenly Father invites us to him, that, refreshed by communion with him, we may ever and anon gather new vigour until we reach the heavenly immortality. But as this mystery of the secret union of Christ with believers is incomprehensible by nature, he exhibits its figure and image in visible signs adapted to our capacity, nay, by giving, as it were, earnests and badges, he makes it as certain to us as if it were seen by the eye; the familiarity of the similitude giving it access to minds however dull, and showing that souls are fed by Christ just as the corporeal life is sustained by bread and wine. We now, therefore, understand the end which this mystical benediction has in view—viz. to assure us that the body of Christ was once sacrificed for us, so that we may now eat it, and, eating, feel within ourselves the efficacy of that one sacrifice,—that his blood was once shed for us so as to be our perpetual drink. This is the force of the promise which is added, “Take, eat; this is my body, which is broken for you” (Mt. 26:26, &c.). The body which was once offered for our salvation we are enjoined to take and eat, that, while we see ourselves made partakers of it, we may safely conclude that the virtue of that death will be efficacious in us. Hence he terms the cup the covenant in his blood. For the covenant which he once sanctioned by his blood he in a manner renews, or rather continues, in so far as regards the confirmation of our faith, as often as he stretches forth his sacred blood as drink to us" (Jean Calvin and Henry Beveridge, Institutes of the Christian Religion, IV, xvii, 1; emphasis mine)."The Lord's table is more than just a commemorative ceremony; it's a means of grace by which we are drawn into intimate fellowship with God.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)