Christianity Today recently began a series on the topic, “Is Christianity Good for the World?” – a subject which turns out to relate to my previous post more than tangentially. Pearcey’s main contention, after all, is that the atheistic materialist really has no warrant for lauding lofty humanistic values given their mechanistic and deterministic view of the universe; and this observation has been the focal sticking point of the entire exchange.

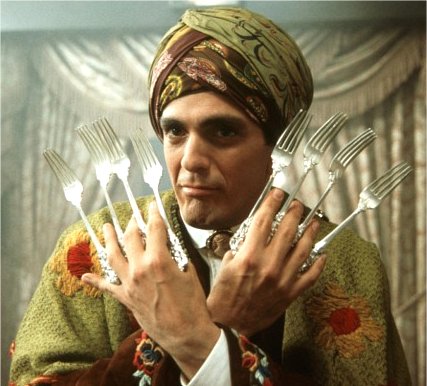

Christianity Today recently began a series on the topic, “Is Christianity Good for the World?” – a subject which turns out to relate to my previous post more than tangentially. Pearcey’s main contention, after all, is that the atheistic materialist really has no warrant for lauding lofty humanistic values given their mechanistic and deterministic view of the universe; and this observation has been the focal sticking point of the entire exchange.The champions called to do battle are an odd pair of obviously mismatched pedigree, an observation humbly noted by the affirmative position (fellow Idahoan, Doug Wilson). Maybe that’s what makes the ensuing discussion such an embarrassment for the negative thus far. Beyond the usual frustration in such “conversations”, where mis-characterizations abound, one gets the distinct impression that Christopher Hitchens is so confident that he’s interacting with an idiot that he doesn’t bother to formulate a single argument. Instead, not unlike our favorite-fork-flinging hero, he unleashes a torrent of verbal cutlery aimed to humiliate the religiously inclined. His attacks are debonair, but rarely of any serious substance – which is where my frustration lies with this larger “down with God” publishing trend we’re seeing lately.

At the point we need philosophers and theologians we are served with self-inflating pundits (or, as in the case of Dennett, philosophers who refuse to engage religion philosophically). Were it not for their impressive vocabularies, it might be more obvious that the “debates” presented in these forums are more like a re-run of Sally Jesse Raphael than they are serious philosophical symposiums. The academic forbearers upon which the edifice of Western society rests (people like Augustine, Aquinas and Pascal) are gaily waved away without protest by people like Hitchens, choosing instead to best Bill O’Reily and Sean Hannity on promotional book tours. The call for a “new enlightenment” conveniently forgets the Christian resources by which we got the first one. He wishes to rise from the ashes of institutions and ideas which, though singed, still stand strong both academically and popularly. Even Nero waited for the city to burn before playing his violin.

Leon Wieseltier’s evaluation of Dennet’s Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomena in The New York Times could just as aptly describe what I’ve seen of Hitchens in this interchange:

Leon Wieseltier’s evaluation of Dennet’s Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomena in The New York Times could just as aptly describe what I’ve seen of Hitchens in this interchange:And Dennett's book is also a document of the intellectual havoc of our infamous polarization, with its widespread and deeply damaging assumption that the most extreme statement of an idea is its most genuine statement. Dennett lives in a world in which you must believe in the grossest biologism or in the grossest theism, in a purely naturalistic understanding of religion or in intelligent design, in the omniscience of a white man with a long beard in 19th-century England or in the omniscience of a white man with a long beard in the sky.If you haven't read the exchange, follow the link and catch up - I'm curious to hear your reactions.

7 comments:

If you can ever get hold of the debates between Hendrik Hart and Kai Nielsen, I think they are worth it. They are found in the books The Search for Community in a Withering Tradition and Walking the Tightrope of Faith

Thanks so much for the recommendation! I'll check it out!

Blue,

Good post. I wonder if you see this "grossest extreme" thing work on both sides of the fence? Clearly, Hitchens is a "gross" materialist, leaving no room for even the *plausibility* of the immaterial (when I say clearly, it's apparent in his exchange here with Wilson, but much more clear in his book and other writings).

But it seems to me just as clear that Wilson here takes a sort of symmetrical "grossness" with his presuppositionalism. For every "faith is ridiculous" from Hitchens, its seems we have a matching "qualitative judgments from you are ridiculous" from Wilson.

I think your paint is well taken, but in my experience one of the major reasons these kinds of exchanges are routinely reduced to exercises in both parties talking past each other is because of the tendency to the "grossest" on both sides. There's little room left for interesting exchange when you categorically rule out the immaterial, even as a *prospect*. Same goes for ruling out the unbeliever's ability to even *deliver* a moral assessment, even *prospectively*, if it isn't pedigreed with a Christian/Calvinist worldview.

Or, is this what the dialog must be: pitting one extreme against the other?

-Touchstone

Thanks, Touchstone. I don't really see a war of extremes here, at least not in the way you suggested. The consistent demand for warrant from Wilson were completely appropriate, in my judgement, given the materialism you mentioned. Requesting the grounds upon which aesthetic and moral judgments can be made seems a far cry from ruling out alternative bases for such deliverances - but Hitchens' refusal to provide any is ultimately the reason the debate never really got going. He could have challenged Wilson's regard for the Bible as some kind of authority about God, but he never pressed that point either.

Blue,

Fair enough. I guess I get bogged down at the point where I think Wilson *knows* better, and is just sort of denying/playing dumb as a defense mechanism or debate tactic. It's completely within his rights to do so, and I'd fully agree that Hitchens completely dropped the ball on that. I just end up thinking: "Wilson knows the answer to his own questions as well as I do". I guess its a stratagem that escapes me.

Anyway, thanks for the response.

-Touchstone

I can see that, and I understand the frustration. Debate strategies make calls for repentance and statements of spiritual concern seem so staged and insincere - but on the other hand, for debate to be effective you have to use rhetoric that forces people to put their cards on the table instead of letting them point at the piano player while they're reaching up their sleeves.

The vocabulary definitely kept the debate from, in my opinion, being a little embarrassing. Wilson made sure to be fairly concise and had more structure to his arguments, making it easy to follow, and the questions being answered apparent. Although, after thinking about why getting Hitchens to give a straightforward, succinct response (at least by the second request) to the right question appeared to be like climbing jello for Wilson (making it hard to get a foothold- I got that from someone else, I'm not clever) is because he wasn't willing to let Hitchen's borrow the terms and their definitions (such as "great" and "good") without giving an account for why he's doing so. In fact, the very title of the book, "God is not Great" causes Wilson to scratch his head and respond, "Great is not, if there is no God." Even the question of topic, "Is Christianity Good for the World?" was interesting. Because Hitchens immediately starts to answer the question- he's assumed a definition for the terms of the question (I say assumed because when called on it he wasn't able to defend it, or maybe he was able but didn't demonstrate that he was). So really, the conversation never even left the ground because the question at hand backed up into another question- I don't know if I'd call it a loaded question (such as, if someone asks you to the contrary "So, have you told your wife you cheated on her?" Either way you answer 'yes or no' you've assumed that you cheated on her), but it already assumed the word "good" and that may have been a mistake- perhaps such a question as "What Does Christianity Do for the World?" -I don't know.

But I did like that Wilson still answered the question even though Hitchens, according to the argument, wouldn't really be able to understand the question. I still liked the exchange, I thought it was good and covered some interesting ground.

Post a Comment